1999

February 21, 1999 - Sumter & Marengo Co, AL

Richard Thurn of the University of West Alabama led the group of 18 members on an excellent day-long field trip to several sites in Sumter and Marengo counties. He started the day inside with a showing and explanation of the various fossils in the display cases at the science building on the campus of the University. The next two stops were at roadside chalk gully formations easily accessible and illustrative of the variety of fossils in the area representing Late Cretaceous snails and oysters.

The third stop was an optional one which everyone took advantage of: a trip to Moscow Landing on the Black Warrior/Tombigbee River, site of an outcropping of the K-T boundary. The chalk on the river bank was very slippery due to the recent rains, but, with the help of Richard's "always take it along on field trips" handy-dandy rope, the attendees was able to get to descend to the river's edge and to observe the K-T boundary. They also spent time collecting fossils in the Late Cretaceous and a few fossils from the Tertiary.

The last stop also was an optional one which 8 people took advantage of: a stop at a road cut on Highway 28 in Marengo County near Jefferson, Alabama. At this site there is an outcropping of the Tertiary and farther down the road there is an outcropping of the Late Cretaceous. The interesting feature of this site is that in between the two areas, there is a good outcropping of the K-T boundary. Additional collecting was done in the Cretaceous layers with everyone finding a good variety and quantity of representative fossils.

March 27, 1999 - Jefferson Co, AL

Department of Physics and Astronomy

University of Alabama

Tuscaloosa, Alabama

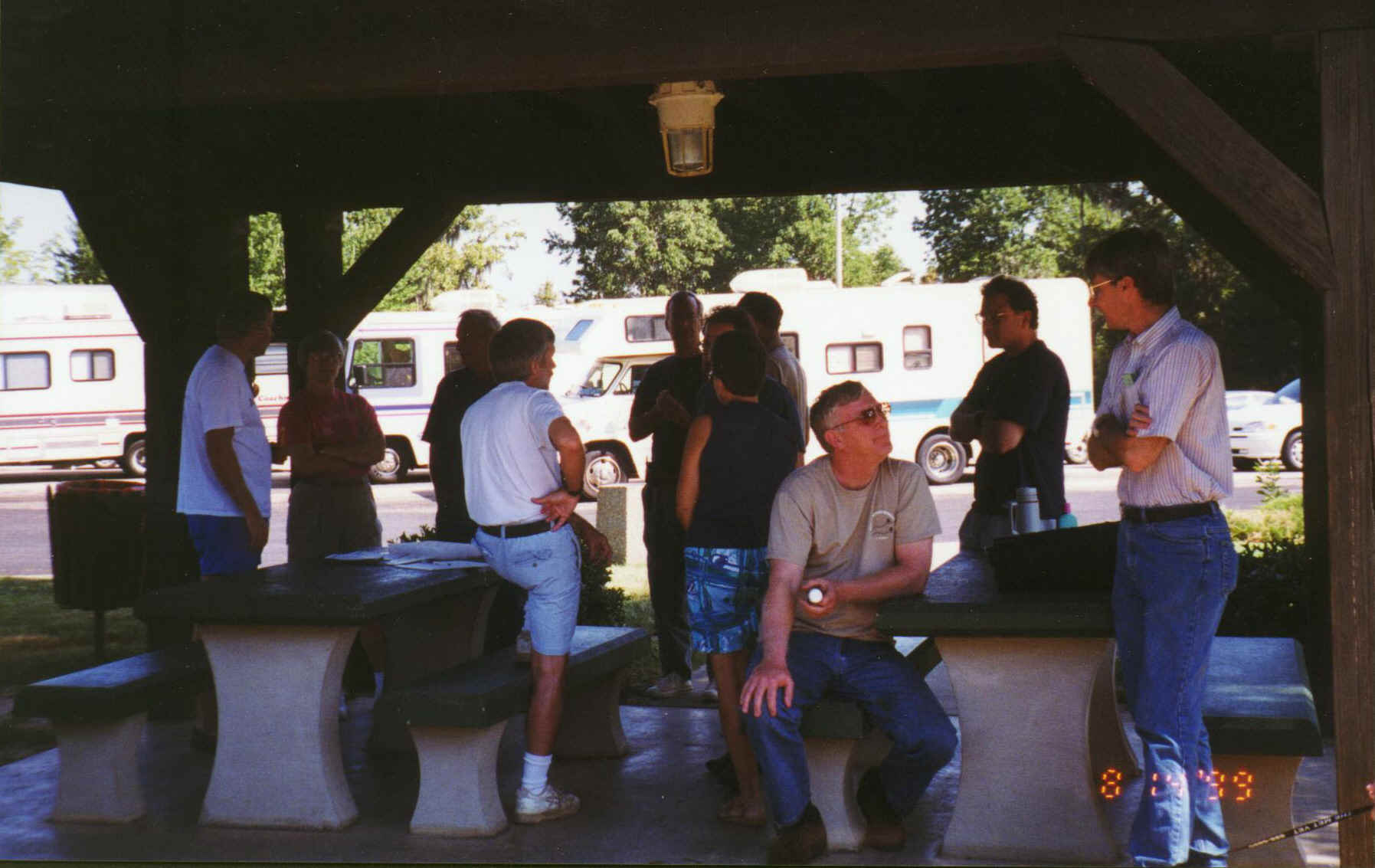

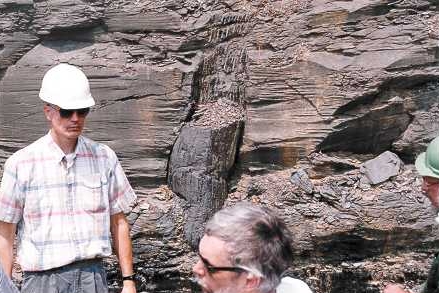

The field trip on March 27, 1999 was the second organized BPS trip to a construction site near Warrior. The trip was attended by about 25 people, mainly from Birmingham, Huntsville, Tuscaloosa, the Florence area, and the University of North Alabama. Attendees included BPS members, guests, children, professors, and students, and the day was sunny, clear, and warm.

|

|

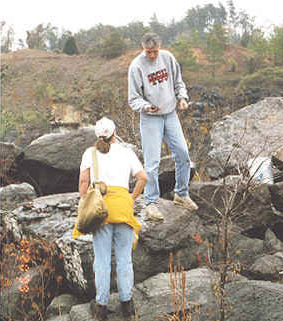

| Fossil hunters at the main rock pile where Lepidodendron and Sigillaria specimens were abundant. |

|---|

The site was first identified as being a source of Carboniferous-period plant fossils by BPS member Gerry Badger, and the first BPS field trip to the site took place on November 15, 1997. Although various BPS members and probably others have visited the site at various times during the past year, the site has changed so much that on March 27, the site was better than it had ever been before as far as numbers and quality of plant fossils are concerned.

The most abundant plant fossils found during our most recent visit were bark impressions of the giant arborescent lycopods Lepidodendron and Sigillaria. These were mainly found in rock piles around the area of a northeast wall of rock. Large slabs showed the familiar Lepidodendron leaf scars, which look like fish scales. In many cases the scars were clear and well-defined, making the specimens extremely beautiful examples. On close inspection, the leaf scars show characteristic bundle and parichnos scars representing leaf attachment points, and many of the pieces are probably of the same species. However, after checking various books I have not yet identified the exact species at Warrior. It is clear also that more than one species of Lepidodendron is present at this site. It is also interesting that specimens of Lepidodendron at Warrior came in both direct and inverse impressions. In direct impressions, the leaf scars are raised, and are more like molds of the original object. In most pieces, however, the leaf scars are simply inverse impressions of the original raised scars, and therefore appear as depressions in the fossil.

| ||

Also abundant at this site, but not necessarily found in the rock piles, were several types of seed ferns characteristic of the period. These were found at a specific level of the east rock wall less than a foot above the ground level and about 20 feet from the rock piles. The ferns found included beautiful examples of Eusphenopteris, Mariopteris, Neuropteris, and Alethopteris form genera, but I have not yet determined exact species. Because many of these were found in situ, they were still beautifully preserved with dark carbonaceous remains of the original plant material and fine details of vein systems in individual pinnules. Several attendees spent much of their time searching for ferns at the rock wall, and many were found. According to Dave Kopaska-Merkel, one young person, whose first name was Jonathan, split a large slab and found some very nice large ferns inside. Although I am not aware of any examples found during this trip, the site also is known for having Lyginopteris ferns which are distinctly different from the others. Several different species of Sphenopteris ferns have also been found in the past.

| View of rock wall on east side of site where ferns were found in situ. |

|---|

| Typical example of a set of ferns extracted from the above part of the wall. |

|---|

Fossils of the well-known horsetail, Calamites, have also been found in abundance at this site. Several attendees (including myself) found three-dimensional Calamites stems further down the same rock wall where the ferns were found. Dave Kopaska-Merkel found a nearly foot-long Calamites specimen embedded in a larger rock. Also found were excellent specimens of the foliage of Calamites, including a fine small piece of (probable) Asterophyllites equisetiformis shown to me by Gerry Badger. At least three different species of Asterophyllites have been found at this site.

was at great risk since the specimen was under a large rock overhang! The job was not easy and afterward I saw the specimen in pieces in the back of Gerry's car, but he still was upbeat about it.Later, I found another stump fossil in a rock wall on the north side of the main site level. It, too, was the only fossil noticed in that particular area, although several of us thought we saw the end of a highly flattened stump still in the wall but much higher up in the same area. The stump I found is about a foot long and weighs 77 pounds. Unlike the others found, it is covered with hundreds of small scars and impressions, indicating a fairly definite identification as an arborescent lycopod cast. These "stumps" and logs represent cases where a hollow cavity left by the stem was filled with mud which later solidified and preserved the general shape as well as any inner details. They are not "petrified" in the usual sense.

In summary, this field trip was a very enjoyable experience for all who attended. On a wonderful day, we all experienced a part of Alabama's past and took home the beautiful relics of a bygone era of Alabama natural history. | ||||||

| Group working on Stigmaria fossil near road to upper level of site. |

|---|

April 24, 1999 - Carboniferous Fossils - Jefferson Co, AL

The Shoal Creek Mine is a modern, high-tech coal mine, having begun operation only 5 years ago. Following an introductory safety presentation (mandatory for visitors to the underground workings of the mine), and a fitting of personal safety paraphernalia (hardhat with light, steel-toed rubber boots, and an emergency "self-rescue unit" to remove carbon monoxide from the air in case of fire), we descended about 1900 feet below the surface in a speedy elevator. Once there, we were ushered into several Humvees, the standard mode of motorized travel through the mine's vast network of tunnels. We then drove several miles to see one of the areas being actively mined.

In the Shoal creek mine, coal occurs in two narrow nearly horizontal seams, named the Mary Lee and Blue Creek seams. The rock just above and below the seams is a sandy shale bearing plant fossils, as we discovered at one stop in the underground tour. Two types of mining techniques are used in the mine, continuous mining and longwall mining. Continuous mining machines tunnel directly into the rock, and have been used to form a network of tunnels. In the longwall operation we witnessed, a line of automated shields support the mine ceiling just next to a long (typically a thousand feet) rock face, while a drum shearing machine moves slowly along the length of the wall, continuously gouging about 39" of rockface off and dumping it onto a continuously running chain conveyor belt. The belt delivers the mixture of rock and coal to a continuous rock crusher, and the chain conveyor then connects with a series of conveyors, the last of which carries the coal and rock to the surface along an exit tunnel sloping up to the surface at a 17 degree angle. At the surface, a series of operations separates rock from coal, and sorts coal into sizes appropriate for different uses. The principal customer for the coal from the Shoal Creek mine is Alabama Power Co.

Many of us were quite impressed with the efficiency of the operation and the thorough measures in place to ensure the safety and comfort of the miners. The mine visit was an outstanding educational experience. In fact, it was also a lot of fun. Our thanks to the Drummond Company, the courteous and helpful mine management and miners, and to Bill Newman, who made the arrangements for the tour on behalf of BPS.

May 29, 1999 - Carboniferous Fossils - Jefferson Co, AL

Department of Physics and Astronomy

University of Alabama

Tuscaloosa, Alabama

The field trip on May 29, 1999, was to an abandoned strip mine in Kimberly that is now being re-excavated by the owner of the Warrior site which was described in the report of the March 27, 1999, BPS field trip. This is a new site for the BPS and we were most likely the first people to seriously look for fossils in the area, at least since the mine was active.

Although the postcard for the trip stated that we would be visiting the same Warrior site as on March 27, it was understood at the last BPS meeting that we would visit the new site and check it out. We decided to visit the new site first and left it as an option for attendees to visit the site on their own, since that site is much easier to find. About 15 people, including BPS members and guests, attended today's field trip.

--Edited by Vicki Lais

The site turned out to be a particularly good one for finding a variety

of Carboniferous period plant fossils. The area was so vast that even

with 15 people we really did not explore it all. Many rock piles

surround an open area where we could park our vehicles. Fossils of

Calamites, including 3D stem casts, stem impressions, foliage, and

cones were abundant in some areas. The site turned out to be a particularly good one for finding a variety

of Carboniferous period plant fossils. The area was so vast that even

with 15 people we really did not explore it all. Many rock piles

surround an open area where we could park our vehicles. Fossils of

Calamites, including 3D stem casts, stem impressions, foliage, and

cones were abundant in some areas.Ferns seemed less abundant, but good specimens were found nonetheless. Finely detailed fossils of the top foliage of arborescent lycopods were found in abundance. Bark impressions of Lepidodendron and Sigillaria were also found. The main difference between this site and the Warrior site is that the fossils at the latter site are concentrated in a small area that is easy to explore. At the Kimberly site, the fossils were spread out over a much larger area and finding them required a great deal of tenacious searching. Also, since you could not necessarily drive your vehicle up any of the steep hills, carrying a large fossil to your car was challenging to say the least. |

There were numerous highlights of this trip. One attendee showed me a

rare (so far as I know) cast fossil of a small part of a stem of

Cordaites, a gymnospermous tree with no modern relatives. The stem of

this tree consists of a series of horizontal ridges and is easily

distinguished from Calamites, but I had never seen one this nice

before. Some very nice pieces of Calamites itself were found. The

inimitable Ken Hoyle showed several of us two spectacular Calamites

casts he found, each about 6 inches long and 4-5 inches in diameter.

The two pieces were obviously part of the same plant, but he could not

find any of the missing parts. There were numerous highlights of this trip. One attendee showed me a

rare (so far as I know) cast fossil of a small part of a stem of

Cordaites, a gymnospermous tree with no modern relatives. The stem of

this tree consists of a series of horizontal ridges and is easily

distinguished from Calamites, but I had never seen one this nice

before. Some very nice pieces of Calamites itself were found. The

inimitable Ken Hoyle showed several of us two spectacular Calamites

casts he found, each about 6 inches long and 4-5 inches in diameter.

The two pieces were obviously part of the same plant, but he could not

find any of the missing parts. | ||

Steve, Dena, and Molly Hand were

also very successful in finding good 3D casts of Calamites, as well as

a nice piece of Asterophyllites equisetiformis, the characteristic

foilage of the branches of Calamites. Ken Wills, who previously spoke

to the BPS last year, found a nice piece with many Calamostachys

impressions, representing the cones of Calamites. Christina and Larry

Hensley found a big rock with a stunning impression of the bark of a

Lepidendron arborescent lycopod. It was beautiful but too big for

anyone to carry. 3D casts of the rhizophore of Stigmaria ficoides, the

root system of arborescent lycopods, were also found by several

attendees, including myself. The largest, 15 inches long, was found by

Bruce Relihan.

|

In summary, this was quite an interesting field trip. When I first "scouted" out this site in April, I was not sure we would find much since casual searching during a period of one hour did not reveal many fossils. The intensive searching by attendees on this trip was much more revealing about the site, and showed it to really be nearly as good as the Warrior site. It will be worthy of a second visit in the future. |

July 24, 1999 - Pennsylvanian Fossils - Walker Co, AL

Department of Physics and Astronomy

University of Alabama

Tuscaloosa, Alabama

This field trip was a very special one for the BPS. We visited a surface coal mine in Walker County. About 20 BPS members and guests attended the trip, which occurred on one of the hottest and most humid days of the year thus far.

This is one of the largest surface coal mining operations in the state. The area is part of the major Pottsville Formation, and is also known as the Warrior Basin. The BPS was hosted by Mr. Hendon, a mine engineer, who also brought his son along. Mr. Hendon first gave us a basic description of the mine, its history, its extent, and the geology of the area. He then took us on a tour of the mine, allowing us to park near a monster machine known as a "dragline". To access the coal seams, overlying soil and hard rock has to be removed, which is the principal task of the dragline. Usually there are 100-200 feet of solid rock to be removed, but on Saturday the dragline was mostly removing topsoil.

--Edited by Vicki Lais

In summary, this was a really great field trip for the BPS. If it had not been so hot, it might have been even better!

|

August 15,1999 - Covington and Escambia Co, AL

Edited by Vicki Lais

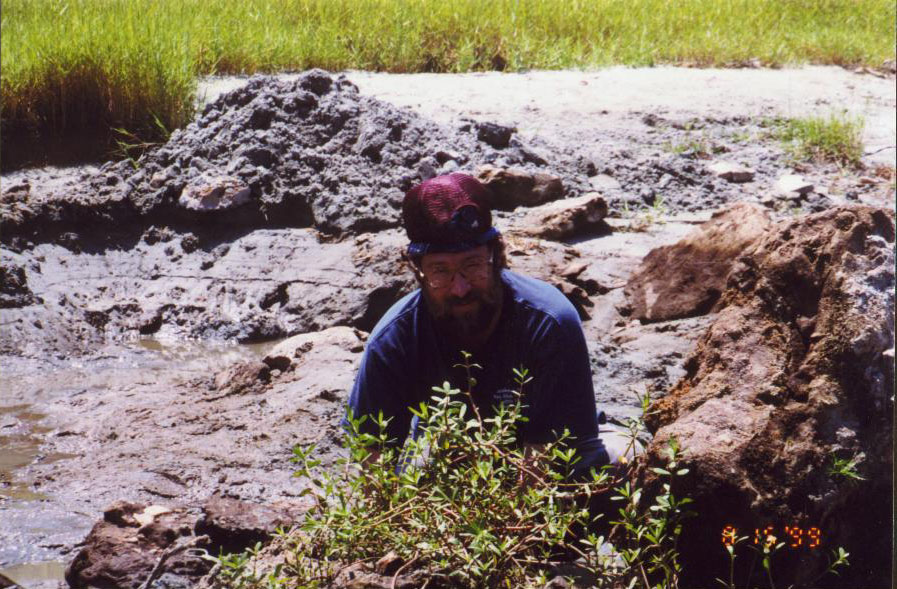

The field trip had two parts. First, we visited a well-known river site in Covington County where shark and ray teeth are present in great abundance, in the lower Tallahatta Formation. Then, we visited a small museum owned by a private collector near Andalusia, in Escambia County. The trip was attended by 20 BPS members and guests on a hot, but not so humid, mostly clear day.

According to Dr. David C. Kopaska-Merkel of the Geological Survey of Alabama, the lower Tallahatta Formation is early Eocene, or about 50 million years old. He says that the formation is slightly younger than the famous Bashi Marl shell bed, and older than the even more famous Gosport Sand shell bed.

According to Dr. David C. Kopaska-Merkel of the Geological Survey of Alabama, the lower Tallahatta Formation is early Eocene, or about 50 million years old. He says that the formation is slightly younger than the famous Bashi Marl shell bed, and older than the even more famous Gosport Sand shell bed.

The site is a well-known collectors area that was visited by the BPS previously in August 1998. The site has mostly shark and ray teeth preserved in a gray sand on the bank of the Conecuh river. The area has been visited so much that large holes pocked the bank where people had previously searched. Apparently, there is some commercial interest in the area, with people digging for large teeth for jewelry to sell, and leaving the smaller items in "spoil piles" of mud. Many of the attendees searched these piles with some success.

The most abundant fossils seemed to be teeth of sharks, with perhaps up to 11 species represented according to one collector, who told me that he visited the area about 3 times a month.

The most abundant fossils seemed to be teeth of sharks, with perhaps up to 11 species represented according to one collector, who told me that he visited the area about 3 times a month.

Dave Kopaska-Merkel told me that he found teeth of tiger sharks and at least 3 other kinds at this site, and saw a 5th kind. Most of the teeth I found seemed to be of the upper jaw variety, where there is a single broad cusp, at least two smaller accessory cusps, and a broad, symmetric root with a dip in the middle. These upper teeth are distinct from those of the lower jaw, which have a longer, narrower primary cusp, clear narrow ridges along this cusp, and a somewhat U-shaped root. No significant accessory cusps are usually seen on these teeth. I noticed that while most of these lower jaw teeth were black, some were actually light brown in color.

These are probably weathered examples, and often were missing part of the U-shaped root.

Next to the shark teeth, the most abundant teeth were those of rays. Unlike the shark teeth, which are also abundant at late Cretaceous sites in Greene County, the ray teeth seem to favor the Eocene site. On asking Dave Kopaska-Merkel about the difference, he offered the following speculation:

"I think most rays are bottom dwellers in shallow water, so if the Greene County site represents a relatively deep water deposit, then there might be relatively few ray teeth there. Also, I think ray teeth are slightly more fragile than shark teeth."

I am not sure what type of rays had the teeth we all found. Most of the ray teeth are elongated rectangles with narrow parallel ridges cut perpendicular to the long axis. At least one ray tooth that I found was notably curved.

Certainly other types of fossils are represented among the hundreds of items people have been finding at this site. One attendee showed me what I think was a small part of a turtle shell, and several likely fish vertebrae were found, one with fragile stems still connected. Bone fragments, sawfish spines, and shark vertebrae were also found, the latter being distinctly circular and somewhat concave-shaped. Some fragile coral specimens were found that came from points higher up on the embankment, which exhibited abundant well-preserved burrows, according to Dave Kopaska-Merkel.

Certainly other types of fossils are represented among the hundreds of items people have been finding at this site. One attendee showed me what I think was a small part of a turtle shell, and several likely fish vertebrae were found, one with fragile stems still connected. Bone fragments, sawfish spines, and shark vertebrae were also found, the latter being distinctly circular and somewhat concave-shaped. Some fragile coral specimens were found that came from points higher up on the embankment, which exhibited abundant well-preserved burrows, according to Dave Kopaska-Merkel.

The high point of this field trip was without a doubt the BPS's visit to view the collection of shark teeth, marine organisms, marine mammal bones, and ice age fossils owned by Mr. Hoomes, a local contact.

Mr. Hoomes is an example of someone who developed a 21-year long interest in fossil collecting after a chance encounter with an unfriendly shark tooth in a creek near his parents home when he was 7 years old. While ambling around in the creek, he stepped on something sharp and thought he had cut himself on some glass. It turned out that he had stepped on an ancient shark's tooth, about one-half to one-inch long, that was standing roughly upright in the creek. (He now wears this tooth on a trademark hat.) He later did more exploring and discovered that shark teeth and other items had a habit of collecting into "potholes" around limestone embankments, and he became very good at recognizing the right places to look for such things. In two of his display cases, he had dozens of large shark teeth beyond anything which most of us had ever seen. To say it was merely an impressive collection of such teeth would be an understatement. Mr. Hoomes also had on display large whale vertebrae and jaw bones, probably from the same period as the sharks teeth.

Especially interesting were Mr. Hoomes's ice age fossils. A humpless camel tooth, bison fossils, horse teeth, and many other items lined his many shelves. Mr. Hoomes also related to us his discovery of bones and stone implements at a likely "kill site" where early humans attacked and killed a mammoth. He showed us artifacts in the form of triangular bone fragments which had been made into likely primitive weapons by the ancient people of the area.

Especially interesting were Mr. Hoomes's ice age fossils. A humpless camel tooth, bison fossils, horse teeth, and many other items lined his many shelves. Mr. Hoomes also related to us his discovery of bones and stone implements at a likely "kill site" where early humans attacked and killed a mammoth. He showed us artifacts in the form of triangular bone fragments which had been made into likely primitive weapons by the ancient people of the area.

Mr Hoomes said he has explored many of the rivers within a five-county area around his home and his vast experience clearly showed in the things he told us.

His collecting has gone beyond what most of us do, and has included searches in remote creeks, not-easily-accessible embankments, and occasional encounters with alligators!

In summary, this was again an excellent field trip for the BPS. Thanks to James Lowery for arranging the trip, and thanks to Mr. Hoomes for taking us on a fascinating journey into Alabama's past! Thanks also to Dave Kopaska-Merkel of the GSA for his comments on this report, which improved its accuracy, and to Jim Lacefield for supplying all of the above images.

Following photos courtesy Larry Hensley.

|

The three people in the foreground are James Lowery with his back to the camera, Jim Lacefield, seated, and Ron Buta, arms folded and deep in a serious discussion of paleontology. |

|

|

|

The Hensley Family |

|

David Kopaska-Merkel |

|

Henry Edmonson |

|

Ron Buta (facing the camera) |

|

David Shepherd |

|

Bill and Kate Newman |

|

Fossils found included sharks teeth, ray teeth, petrified wood, and vertebrae of sea snakes. The time period represented in the site we worked was the Eocene, the early age of Mammals, approximately 40-50 million years ago. From this site we proceeded to a private museum. A fascinating exhibit!

November 20, 1999 - Bibb Co, AL

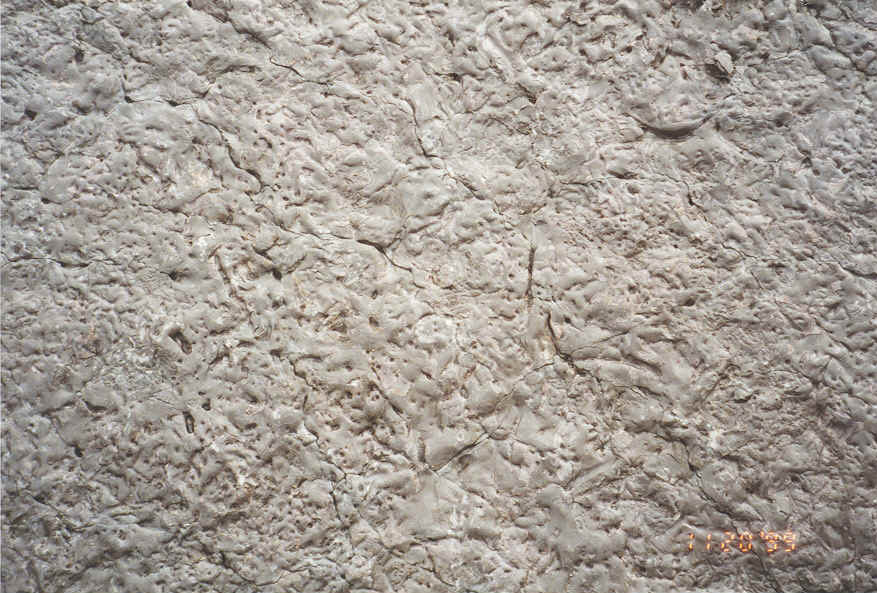

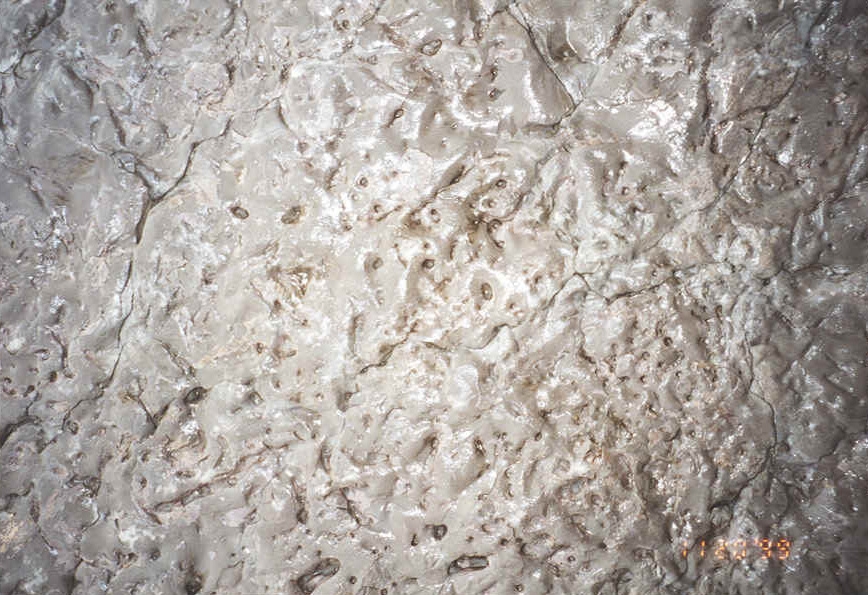

|

This Saturday field trip was the first visit even by veteran BPS members to a quarry located in north Bibb County. The rocks from this quarry have been used as rip-rap at several highway locations, the best ones I know of being on a ramp at Exit 79 and between Exits 77 and 79 on I20/59 near Tuscaloosa. |

The trip was attended by 20-25 BPS members and guests on the first rainy day we had in nearly three weeks. This quarry is a largely abandoned location where rocks of middle Ordovician age (460-480 million years) have been exposed. The rock formations at this site are part of the well known Chickamauga Limestone Group. The main quarry pit is now a small lake filled with deep-looking water having a strong aquamarine color. The lake is surrounded by steep cut cliffs. Rocks are scattered in large piles around a wide area near the lake, and it was among these piles that BPS members searched for fossils of mostly marine animals. In spite of the vastness of the area, it took some tenacity to find fossils since fossiliferous rocks were not that common. |

|

| Fig. 2 - Group discussing strategy for exploring the area. |

|---|

|

| Fig. 3 - View towards rock piles around the lake. |

Apparently, it is the fossils themselves that tell us the age of the rocks at this site. According to Prof. Carl Stock of the University of Alabama Department of Geology, the main index fossils are conodonts, which are very small, sometimes cone-like objects whose nature is not well understood. I am not sure that any of us noticed such fossils, but a magnifier would probably be needed to see them in any case. More obvious index fossils found in quarry rocks are brachiopods. According to R. Wixon (University of Alabama master's thesis, 1984), Ordovician brachiopods are good index fossils because of their abundance worldwide and the short period of their evolutionary timescale. Well-preserved brachiopods of clear middle Ordovician age are found at the quarry and at the I20/59 sites.

Many of the brachiopods that we found at the quarry appear to belong to the order Strophomenida which, according to The Fossil Book by Rich, Rich, Fenton, and Fenton (1996), are frequently referred to as "petrified butterflies". There are many genera and species in this order of articulate brachiopods, and I could only identify a few in the rocks that I personally picked up, based on illustrations in Wixon's thesis and Volume H of the Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology (Moore, editor, 1965). A few are shown in the illustrations here. Larry Hensley found a large slab covered with brachiopod shells mostly about 1 cm in diameter each (see photo). Several of us managed to hammer away at this large rock and get some pieces of it. Many of the brachiopods on this slab appear to be of the genus Sowerbyella. |

|

| Fig. 6 - Medium-sized brachiopod, probably of genus Rafinesquina, with smaller Hesperorthis australis brachiopods to upper right and left |

|---|

|

Larger brachiopods about 2.5 cm or so in diameter seemed less abundant than the 1cm or smaller pieces. The one I show here, shaped sort of like a tombstone, is probably of the genus Strophomenus or, more likely, Rafinesquina. The largest brachiopod I found is more than 3cm in diameter, and may be of the genus Tetraphalerella, whose members can get this large according to Wixon. Other fossils found include the stems of crinoids, random stem plates of dis-assembled crinoids, bryozoans, parts of trilobites and, I heard, cystoids. Trace fossils of worm burrows were actually among the easiest fossils to find at this site. A large slab covered with criss-crossing tracks is shown here. Don McDonald also showed me what he thought was the end of a horn coral, and Vicki Lais showed several of us a very large rock having some interesting spiral-shaped fossils that we could not identify. Apparently, someone had previously used a rock saw to cut out a piece of this same rock. |

|

|

Although it was not easy finding fossils at this site, it was clear that everyone who attended the field trip had an enjoyable time. The area was interesting and the rocks mysterious, being older than most of those exposed in regions north and south of the site. The key to success at a site like this is to have a lot of time to explore and to be prepared. I regret that I had not studied any of the books I mention above until AFTER I got home! --Edited by Vicki Lais |

December 18, 1999 - Pennsylvanian Fossils, Walker Co, AL

|

During this field trip, the BPS had the pleasure of returning to the Cedrum Surface Coal Mine near Jasper in Walker County, Alabama. Although we had visited this mine only a few months ago (see BPS field trip report for July 24, 1999), there was a sense of urgency connected with our latest visit. The Drummond Company, which operates the mine, was going to shut down operations on December 30, which would then be followed by the normal reclamation effort to restore the area. This meant that the large "spoil piles" we explored in July would soon be gone. Thus, it was decided that we should go back one more time before the reclamation effort to look for plant fossils.

As in July, this visit was hosted by a mine engineerwho instructed us in issues of safety in the mine area. We were delighted to have his wife join us this time and bring several parents and students of various ages who are involved in home schooling. They all seemed to enjoy learning about fossils and to be excited about finding and collecting them. During this visit we had about 30 BPS members and guests in attendance, a larger than average group. There were so many cars that we were asked to carpool a little to miminize the number of cars in the pit. |

|||

|

I must say that I enjoyed this visit much more than the visit in July. The highlight of the visit in July was our tour of the mining operation and our visit to the "dragline." However, it was so hot that day that fossil collecting was difficult and a little unpleasant. Our focus this time was only on fossil collecting, and the day was cool, calm, a little cloudy, and very pleasant for climbing and searching the rock piles. We also collected in a different area from our July visit. One problem we encountered was that it was rather dry, and the movement of trucks combined with dryness caused the rocks to be very dusty, making it a little difficult to notice the fossils. Thus, it was not especially easy to find good fossils.

Many of the fossils that attendees did find were very good. I can describe a few that I brought home. Being a little slow in heading towards the main rock piles, I stopped at a rock that others had seen but had passed up because of its size. The rock included a foot-long Calamites pith impression that I thought was interesting because it includes about 20 nodes. There is more than just the pith, however. The pith is surrounded by a wider pattern that may give the true dimension of the trunk, since the sediment was obviously impacted by the plant over this wider area. The specimen looked much better after it was cleaned, and I show a picture of it here. |

|

|

|

|

Don McDonald found a rock with what looked like nice specimens of Asterophyllites, one of the forms of the foliage connected with Calamites. The rock was very large and it was difficult to extract intact pieces.

This nearly happened to me on the next fossil I found. Near where Don was working, I found the interesting fossil shown here. It broke up when I started to try and extract it, but the pieces could be put together like a puzzle as in the photograph. At first, I thought this was a Calamites impression, but the long striations and the narrowing of the fossil towards its end reveals this to be a giant strap-shaped leaf of Cordaites. Note the lack of any nodes, which rules out the Calamites interpretation completely. Matthew Valente, who came as a guest with Jim and Faye Lacefield, found a round-leafed fossil fern that I had not seen before. Matthew tentatively identified it as Mariopteris robusta. According to Jim, this is a common species near the south part of the well-known Warrior Basin, but it is not common in Walker County where Cedrum is located. This field trip was combined with our traditional "Christmas season gathering" and several members brought the fixings for our lunch that were shared by everyone. Thanks to Jim Lacefield and James Lowery for comments and additions to this report, and especially to Steve Minkin and his son for making and bringing the delicious gumbo as our main course! --Edited by Vicki Lais |

Photos

by Larry Hensley

|

| Cedrum Surface Mine in Walker Co., Alabama, Dec. 18, 1999 -- BPS Members in the Huge Dragline Bucket |

|---|

|

| |

|---|

|

| |

|---|

|

| |

|---|

|

| |

|---|

|

| |

|---|

|

| |

|---|

|

| |

|---|

|

| |

|---|

|

| |

|---|

The machine uses a 180 ton metal bucket to drag soil and rock forward

for lifting, and then rotates to dump the material on an area that has

already been mined. The machine is so large and so specialized that,

according to Mr. Hendon, it cost $36 million when it was brand new. Not

only were we allowed to view the dragline from close up, but we were

also able to go inside and see how it works. The movements of the

bucket can be efficiently operated by one person, but three other

workers are usually present to keep the machinery functioning and

oiled. The complex manipulations of the dragline depend on 16 giant

motors of over 100 horsepower each, one of which we saw winding and

unwinding the huge cables connected to the bucket. Other motors rotate

the whole assembly and move it. We all visited the operator control

room, as well as a second empty control room. Inside the machine, the

noise was loud enough to necessitate the use of earplugs. After

visiting the dragline, Mr. Hendon took us all to a second bucket no

longer in use, where I took the group photograph shown here.

The machine uses a 180 ton metal bucket to drag soil and rock forward

for lifting, and then rotates to dump the material on an area that has

already been mined. The machine is so large and so specialized that,

according to Mr. Hendon, it cost $36 million when it was brand new. Not

only were we allowed to view the dragline from close up, but we were

also able to go inside and see how it works. The movements of the

bucket can be efficiently operated by one person, but three other

workers are usually present to keep the machinery functioning and

oiled. The complex manipulations of the dragline depend on 16 giant

motors of over 100 horsepower each, one of which we saw winding and

unwinding the huge cables connected to the bucket. Other motors rotate

the whole assembly and move it. We all visited the operator control

room, as well as a second empty control room. Inside the machine, the

noise was loud enough to necessitate the use of earplugs. After

visiting the dragline, Mr. Hendon took us all to a second bucket no

longer in use, where I took the group photograph shown here.

One of the most interesting fossils I noticed at this site was a

modest-sized bark impression of Lepidophloios, a subgenus of the

Lepidodendra. The leaf scars of Lepidophloios are very much like those

of a normal Lepidodendron stem, only the scars are elongated

horizontally, rather than vertically. Although I have read that fossils

of Lepidophloios are the most commonly found plant fossil in Alabama,

it was the first time I had seen a definitive example. It was easily

distinguished from the better known Lepidodendron.

One of the most interesting fossils I noticed at this site was a

modest-sized bark impression of Lepidophloios, a subgenus of the

Lepidodendra. The leaf scars of Lepidophloios are very much like those

of a normal Lepidodendron stem, only the scars are elongated

horizontally, rather than vertically. Although I have read that fossils

of Lepidophloios are the most commonly found plant fossil in Alabama,

it was the first time I had seen a definitive example. It was easily

distinguished from the better known Lepidodendron.