May 26, 2001 - Greene Co, AL

BPS members collected in a Greene County, Alabama creek. At this Cretaceous site, we found numerous shark and ray teeth and some fish vertebrae.

BPS members collected in a Greene County, Alabama creek. At this Cretaceous site, we found numerous shark and ray teeth and some fish vertebrae.

Track Meet III and the concurrent PlantFest was held on May 12, at the Anniston Museum of Natural History. We spent the day documenting especially fine, well-preserved, interesting plant fossil specimens and previously unphotographed tracks collected at the Union Chapel Mine. We were fortunate enough to have 2 visiting paleobotanists at this Meet. Thanks to all of the organizers and participants!!

BPS members visited two late Cretaceous sites in Montgomery County, Alabama, where we collected primarily shark teeth and echinoids. A pycnodont tooth (rare in Alabama) was found by Vicki Lais.

In 1999, Ed Hooks of the Alabama Museum of Natural History in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, along with David Schwimmer and Dent Williams of Columbus State University, Columbus Georgia, had written an article titled "Synonymy of the Pycnodont Phacodus Punctatus Dixon 1850, and Its Occurrence in the Late Cretaceous of the Southeastern United States". This article was published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology in September 1999. Earlier, Gordon L. Bell, Jr., one of the founders of BPS, wrote an article titled "A Pycnodont Fish from the Upper Cretaceous in Alabama" (pdf link), which was published in Journal of Paleontology, Vol. 60, Sept 1986.

BPS members collected at a Bibb county quarry and nearby graptolite site this month.

ANCIENT ALABAMA ANIMAL TRACKS INSPIRE AMATEUR FOSSIL COLLECTORS

TO DOCUMENT FINDS

"The handprints, which include long, curving toes with easily-distinguished pads on the tips, are nearly as big as my own," exclaimed Dr. Jim Lacefield of Tuscumbia. "This was a huge beast. Although I had read that some amphibians reached rather large size in the Pennsylvanian, in all my collecting in Coal Age rocks in Alabama I have never seen any that were anywhere nearly this large," he said.

Lacefield, a part-time biology and Earth science instructor at the University of North Alabama, and author of a recently published book on Alabama fossils, was describing remarkable fossil footprints of an ancient alligator-sized animal that he had collected at a surface coal mine in Walker County owned by the New Acton Coal Mining Company of Warrior, Alabama. Lacefield was visiting the mine on an outing early last year with members of the Birmingham Paleontological Society (BPS), an active group of local amateur fossil hunters who had received permission from the company to salvage fossils from the area.

The mine had been discovered only a few months earlier to be an unusually good source of fossil vertebrate trackways by Ashley Allen, an Oneonta High School science teacher who is also a member of the BPS. A student in Allen's class had alerted him to the site owned by his grandmother, Mrs. Dolores Reid. Fossils connected with vertebrate animal life (that is, animals with a backbone) are of great paleontological significance since they represent some of the most advanced forms of life that developed on Earth at the time and are usually very rare.

Since Allen's discovery, the Walker County mine has been the focus of an extraordinary salvaging effort by BPS members that has led to a remarkable cooperation with professional paleontologists. The trackways collected from the mine are of vertebrate as well as invertebrate animals that lived during the Late Carboniferous Period of Earth history, known to North American geologists as the Pennsylvanian Period. This Period dates back 310 million years to a time when much of the Earth (particularly North America and Europe) was covered with great tropical swamps that eventually laid down many of the vast coal reserves we use today. (In fact, the Pennsylvanian Period is also often referred to as the "Coal Age.") During the past 15 months, mainly through the efforts of the BPS, more than 800 track specimens have been salvaged from the residual rock piles left after the coal mining was discontinued.

According to Dr. Anthony J. Martin of the Department of Environmental Sciences, Emory University, the Walker County mine is "one of the best vertebrate track sites for the time period in question in the world." Martin is an ichnologist, a paleontologist who studies "trace" fossils, or traces of ancient activity. Tracks are trace fossils since they show what an animal was doing but not specifically what it looked like. Martin became involved in the study of the Walker County mine tracks through the insight of Steve Minkin, an Anniston geologist and BPS member who was very active in collecting trackways from the site. Recognizing the scientific importance of the tracks, Minkin proposed a series of meetings at which amateur collectors would bring all of their track finds from the mine to one place for photographic documentation and detailed inspection by professional paleontologists. The first of these events, jokingly dubbed a "Track Meet", was held on August 19, 2000 at the Alabama Museum of Natural History on the campus of the University of Alabama. Dr. Ed Hooks, Museum curator, fully supported the event and was instrumental to its success. The event was also sponsored by the Geological Survey of Alabama. A second meeting, called "Track Meet 2", was held at Oneonta High School on October 14, 2000 to document all finds since the first track meet. The third and final track meet, called "Track Meet 3", will be held on May 12, 2001 at the Anniston Museum of Natural History and will photographically document all tracks found since Track Meet 2 and since the final reclamation of the mine in December, 2000.

Although no fossils of the ancient animals that made the tracks have been found, the trackways record the dynamics of life on land nearly 90 million years before the first dinosaurs walked the Earth. According to Dr. Jack Pashin of the Geological Survey of Alabama, the tracks occur at the head of an area that was once a tidal mud flat much like the one seen today in Mobile Bay. The environment would have been far enough inland to be fresh water rather than salt water, but it would have been an area still dominated by one or more daily tides. At ebb tide, animals would walk or creep across the still wet mud and impress the tracks of their activities. The mud was soft and fine enough that even small creatures could leave well-defined tracks. The best-preserved tracks were probably impressed so deeply that they were buried before they had a chance to be altered in any significant way. Once buried, they were effectively removed from further disturbance for the next 310 million years.

The tidal flat was evidently near a rich forest of tall tree-like lycopods (primitive spore-bearing plants whose foliage resembled that of modern clubmosses), giant horsetails (plants roughly like reeds or bamboo), and tree-sized seed ferns, because among the tracks BPS members also found bark impressions, pith casts, fern impressions, and reproductive organs of a wide variety of ancient plants that are now extinct. It is known that these types of plants could only thrive in fresh-water swamps. Insect life was probably abundant in the forest, and it is significant that one insect fossil was found at the Walker County mine. Dr. Prescott Atkinson, a Birmingham pediatrician and BPS member, found a pair of 4-inch long wing impressions of an extinct relative of modern dragonflies. This is the only fossil found at the site that gives direct information on the actual appearance of a creature that lived in the area. Because of the high quality of many of the plant fossils found at the same site, Track Meet 3 will include a "Plant Fest", where the best plant specimens from the mine will be photographically documented and examined by professional paleobotanists (scientists who study fossil plant life).

Many of the tracks found by BPS members are of amphibians, animals whose modern relatives include frogs and salamanders. These tracks include striking five-toed patterns over a wide range of sizes from less than a centimeter to the size of an adult human hand. Other tracks are those of animals that may be transitional between amphibians and reptiles. Although we do not know precisely what these creatures looked like, they would have been some of the earliest vertebrates to be fully adapted to dwelling on dry land.

Tracks of other animals, mostly invertebrates, have also been found at the Walker County mine. Apparently, the area was very popular with horseshoe crabs, animals that are related more to scorpions and spiders than to conventional crabs. Today's horseshoe crabs are "living fossils", and the ancient ones that left the tracks probably looked very similar to modern ones. The complex pattern of legs on horseshoe crabs, and the way they walk in water, can explain a wide variety of tracks found at the Walker County mine. Horseshoe crabs in large numbers also left "resting traces", simple impressions of their leg patterns. Evidence also for early fish swimming in shallow areas has been found in the form of wavy tracks where it is thought that fins lightly touched the bottom. Numerous worm burrows have also been found.

All of the trace fossils found at the mine record valuable information on life in the Paleozoic ("ancient life") Era of Earth history. This Era runs from 570 to 245 million years ago, and it was during this time that life on Earth gained a foothold on land. From studies of the tracks brought to the various track meets, ichnologists have deduced that the Walker County mine area was a nursery for many of the animals living there. According to Dr. Andy Rindsberg, an ichnologist working for the Geological Survey of Alabama, the fact that the various tracks occur in a broad range of sizes whose shapes changed slightly as they grew larger points to this interpretation, which is similar to the way modern animals use tidal mud flats today. Rindsberg, along with Martin and his undergraduate student Nick Pyenson, is actively researching the tracks and the team presented talks about them in March to the Southeastern Section of the Geological Society of America.

For the BPS, the discovery of the beautiful trackways has made for a very exciting year. The amateur group, headed by Kathy Twieg of Vestavia Hills (near Birmingham), put a lot of time into salvaging as many tracks as possible before the mine was reclaimed in December. The generosity of the New Acton Coal Mining Company, in particular the enthusiasm of owner Mrs. Reid, was instrumental to the success of the venture. For many of the collectors, the great appeal of the tracks was not only because of their possible scientific value and great beauty, but also because they are more about life than about death. Unlike a pile of bones, tracks record what animals were doing when they were alive. They bring to life an era far removed in time from our own.

For Allen, the Walker County mine experience is part of what being a teacher is all about. "I try to convey to my science students the importance of communication in the scientific community," he says. "I want to be accurate in representing the principles that the scientific enterprise is based upon. Work done without proper communication is called a secret, not a discovery. I feel that any opportunity that I get to show them how to use problem solving skills, scientific reasoning, communication skills, and the ability to put things into a proper social and historical perspective is worth the effort."

The Track Meets themselves represent a rare collaboration between amateurs and professionals that could become a model for other similar finds. "Amateurs are often the source of new discoveries in paleontology," says Rindsberg, who notes that if the BPS had not learned about the site so soon after mining operations ended, any tracks exposed would either have weathered away or been re-buried when the site was reclaimed. He also notes that "if the BPS had not spent so much time looking and splitting open boulders, then the fossils would not have yielded up as much information as they have. Even with the nearly one thousand tracks and trackways that have been labeled so far, Tony Martin and Nick Pyenson have identified some specimens with unique features. If those single specimens had been missed, we would know less about the creatures that made them. At every step of the way, persistence and open-mindedness paid off in this case. I am certain that Alabama has many other surprises for us to find."

To see what some of the tracks look like, click on the following links:

Image 1: Tracks of an amphibian known as Cincosaurus cobbi, a common five-toed animal on the mud flat.

Image 2: Tracks of a larger amphibian, possibly a more grown C. cobbi.

Image 3: Tracks of one of the largest amphibians that walked on the mud flat, known as Attenosaurus subulensis.

Image 4: Tracks of a likely horseshoe crab.

This press release was prepared by BPS member Dr. Ron Buta, a professional astronomer at the University of Alabama. He can be contacted at 205-348-3792 or buta@sarah.astr.ua.edu.

Interested persons may contact Drs. Martin and Rindsberg at the following e-mail addresses:

Dr. Anthony J. Martin - geoam@learnlink.emory.uab

Dr. Andy Rindsberg - ARindsbert@uwa.edu

The following people are either quoted or mentioned above, and may also be contacted for information:

Dr. Jim Lacefield

Dr. Ed Hooks - hooksge@longwood.edu

Dr. Prescott Atkinson - patkinso@uab.edu

BPS members collected in the Bangor Limestone in Franklin County, Alabama, and made several stops at roadcuts

in the area. Specimens from this site date to the late Mississipian

Period of geological history (about 320 million years).

BPS members collected in Cherokee County, Alabama. This site is the Conasauga Formation of the Cambrian, and numerous trilobites were found.

NOTE: We lost server access due to the illness of the administrator of our host server. It was over a year before he was back at work, and no field trip reports were created during that time period. These brief memos are simply place-holders for the trip. Periodically, old photos do turn up and get scanned in.

by Ron Buta, Department of Physics and Astronomy

University of Alabama

Tuscaloosa, Alabama

The Union Chapel Mine is now known to be one of the best Lower Pennsylvanian track sites in North America. During December, the mine was in the process of reclamation, and the BPS returned one more time as a group to search for trackways among turned-over spoil piles in one of the most productive areas of the site. About 15 BPS members and several newcomers attended the field trip on a pleasant mid-December day.

When we arrived at the site, only one small area was not reclaimed. This particular area was one which had yielded many good tracks in the past and so we were all delighted to see that the mine workers had moved some of the old rock piles around, allowing us to see if any new material had been exposed. In spite of this, we all had difficulty finding any new high quality tracks. Nevertheless, there were still tracks to be found. I found the interesting specimen shown in Figure 1. It appears to be the trackway of an arthropod, where each track is a small roundish spot. In the significant collection of track photos which the BPS "track meets" have provided, I had not seen another set like this one. I also found the tracks shown in Figures 2 and 3. |

|||

|

|||

|

|||

| On the reclaimed areas and in the overturned area, one can still find nice plant fossils at this site. Figure 4 shows an especially nice set of ferns from a split rock. Most interesting is how strong the stem of these ferns is.

|

|||

Figure 5 shows brown ferns of the genus Neuropteris, which was common at this mine.

|

|||

Figure 6 shows a single large seed impression of a seed fern. This is how such seeds are often found.

|

|||

However, I found another rock in the overturned area having more than a dozen seed impressions. Several of these are shown in Figure 7.

|

|||

The ferns they are associated with are shown in Figure 8. Jim Lacefield discusses the seeds of seed ferns on page 66 of his new book, "Lost Worlds in Alabama Rocks", and gives a wonderful general discussion of the Coal Age in Alabama and what happened to the seed ferns.

|

|||

The reclamation of the Union Chapel Mine caps off a spectacular year of discovery for the BPS, and the Union Chapel experience marks the beginning of a remarkable cooperation between BPS amateur rock collectors and two professional organizations, the Geological Survey of Alabama and the Alabama Museum of Natural History on this new project. The more than 500 track specimens salvaged by BPS members and guests since January 23, 2000 are currently being researched by professional paleontologists. Hundreds of high quality plant fossils were also salvaged and will eventually be studied. We will no doubt be talking about the experience for years to come.

The publication of Jim Lacefield's new book, "Lost Worlds in Alabama Rocks: A Guide to the State's Ancient Life and Landscapes" led the BPS to this new site for a field trip this month. In previous BPS field trip reports, I have noted the abundant plant fossils that we have found at various surface mines in Walker and Jefferson Counties. These sites include plants from the Coal Age in Alabama, dating back to about 310 million years. It was interesting, therefore, to learn from Jim's book that it was possible to find plant fossils in Alabama from a much later period, the Cretaceous period. Jim agreed to lead the BPS to a site where he had found fossil leaves, dating back to about 85-90 million years (Late Cretaceous). The site is in the Tuscaloosa Group of sediments (the earliest part of the Cretaceous found at the surface in Alabama). About 20 BPS members and guests attended the field trip, which took place on a cool but pleasant and mostly sunny day.

| The site was certainly different from the surface mines. At the surface mines, fossils are usually impressions, molds, and casts in shale, or solidified mudstone. Often, these fossils include the carbonized remains of the original plant material. At the Cretaceous site, however, the leaf fossils were in a light gray mud just a few inches below the ground level, concentrated in a fairly small area near a roadcut. The types of leaves found were almost exclusively angiosperms bearing a strong resemblance to modern varieties. |  |

| Figure 1: Viewing of digging site towards road. The hole is where nice brown Cretaceous leaf fossils were found. |

|

| Figure 2: Group at area where the blacker leaf fossils were found. From left to right: Dave Shepherd, Kathy Twieg, Jim Lacefield, Vicki Lais, and Marcella. |

|

| Figure 3: In the foreground, Ashley Allen is collecting the darker brown leaves. In the background is the group in Figure 2 |

| According to Jim, the angiosperm species included Salix (or willow), which represented greater than 90% of the specimens, and two members of the Lauraceae (or laurel family). The Salix leaves tended to be long and thin with a single dividing vein and very little additional detail. Often, stem attachment points were found, but it was rare to get a complete leaf on one slice of mud. |

|

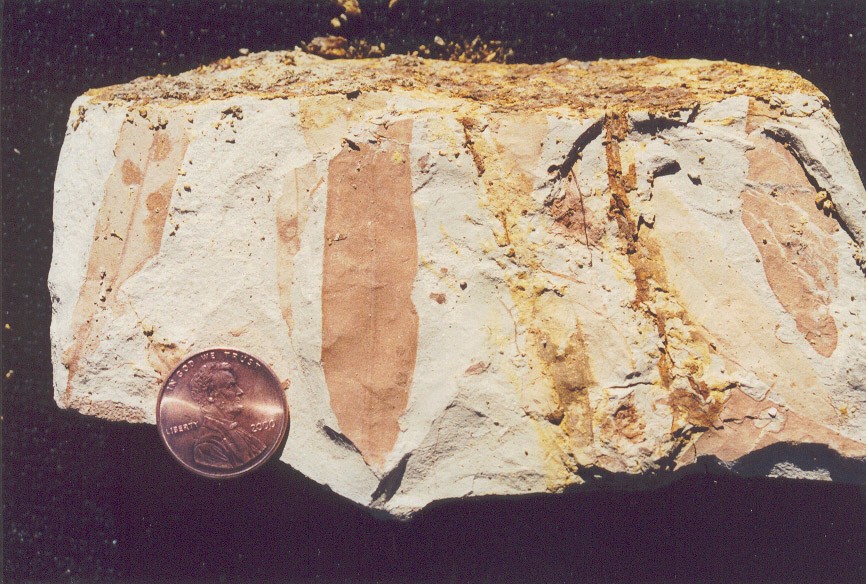

| Figure 4: Examples of Salix (willow) leaves showing the distinctive brown color characteristic of one part of the site. |

| Several examples are shown in the photographs which accompany this report. Some are also shown on page 81 of Jim's book. The Lauraceae leaves tended to be Cinnamomum, a possible Sassafrass. These had a distinctive vein structure which can be seen on page 82 of Jim's book. Jim also found what he thinks are probable flowers in different stages of decomposition, representing possibly 3 different species. The "flowers" he found included a willow twig with catkin attachments (no catkins were found) and two small but identical unidentified (possibly laurel) flowers with crumpled petals. |

|

| Figure 5: One half of a divided mud plane showing beautiful brown Salix leaves. |

| An interesting aspect of the site was how the color of the leaf fossils changed with position. At the left side of the site, the color was a very light brown, while near the middle it was a darker shade of brown. About 20 feet from these areas, the fossils are completely black and often incomplete. Presumably, the color is not the same as the original color, although modern angiosperm leaves look remarkably similar to the dark brown fossils after they achieve their fall color. The best quality fossils were these dark brown ones. |

|

| Figure 6: The other half of Figure 5, showing virtually identical colors and structure, with no sense of direct or inverse impressions being given. |

|

| Figure 7: Beautiful thin Salix leaves. |

The area where these were located was found by Bruce Relihan, who generously shared the find with others. The illustrated specimens are mainly from Bruce's area, and some are very beautiful. Most remarkable is how different these plants are from the coal mine plants. At the coal mine sites, we often find scale tree bark impressions, ferns, and pith casts of giant horsetails. At the Cretaceous site, we mainly found rather normal-looking leaves - no bark impressions and no ferns at all. By this time, many of the Coal Age plants were extinct and had been replaced with more modern-looking species.

| The blacker leaf fossils were more like coal age fossils. These looked like the carbonized remains of the original plants, while the brown ones seemed to have iron deposits replacing the original material. The black fossils seemed more fragmentary, and also more concentrated in random assortments than the brown leaves. In the area where these blacker leaves were found, we also came across what appeared to be lignitized wood. Some of this was layered as in a coal seam. |

|

| Figure 8: Small mud slab showing a mix of black and brown Salix leaves. |

The fact that the fossils were found in clay, and not rock, is certainly interesting. It is difficult to understand this, and it suggests that the area where these leaves lie has not changed much during the past 85-90 million years. If it had been under water, there would presumably have been more deposition over the area and conceivably the clay might have solidified under pressure. Jim thinks the site possibly represents an upland bog in the process of being filled in with fine-particled sediment.

Note that it is also possible to find Coal Age Alabama fossils in clay, as Jim notes on page 65 of his book. The distinctive color of the clay where the fossils were found helped to tell us where to look. Just across the street from the site, we found mostly a reddish clay with a presumably high iron content. However, this clay included no fossils. The gray clay was more homogeneous than this reddish clay, and provided high quality fossils.

Cleaning clay fossils is another issue. With shale, you can simply wash off dirt or scrub off mud with a brush. With clay fossils, washing has the risk of damaging the fossils. The procedure I used to clean the specimens I brought home involved using an air blower usually used to blow dust off of photographic negatives, followed by gentle brushing with a small paintbrush. Even after this, the long-term storage of such fossils may require something extra. When extracted from the ground, the mud was a little wet, but after a while it becomes dry and more brittle. The best time to extract these kinds of fossils is when they are a little wet, because then the mud breaks apart into planes a lot like shale. After drying this might not work. Jim recommended that after the specimens are completely dry, it might be worth placing them into a 50% Elmer's glue for long-term preservation. Jim notes that the clay to be preserved in the Elmer's solution needs to be very close to dry when the solution is applied through soaking for 5 - 10 minutes, otherwise the surface may appear cloudy. He recommends that excess solution be then gently dabbed off the leaves themselves, and further that the specimens should be dried thoroughly before much handling.

In summary, this was a very interesting field trip for the BPS. It was interesting to venture into new territory in Alabama's past, and in particular to focus on the plant life, rather the marine life, of Alabama Cretaceous history. Thanks to Jim for his excellent book and for taking us to the site! I also thank Jim for comments on this report that improved its accuracy.

--Edited by Vicki Lais

This report (installed on Sept. 27) is late because of the month-long trip to South Africa that I took from mid-July to mid-August. As a result, I can only roughly describe what the BPS did this day. There were three sites in Sumter County that were visited, all well-known and previously visited by the BPS.

| There are numerous Late Cretaceous chalk exposures in Sumter Co. One of these is found in a field near Livingston, and includes numerous shells, shell fragments, and other fossils (see Figures 1 and 2). The site is visited annually by various groups, and is known for the tiny echinoids (Boletechinus mcglamerii) which can be found there. Several were found on this day, one of which is shown in Figure 3. |  |

| Fig. 1 - BPS members and guests collecting Late Cretaceous marine fossils. |

|

| Fig. 2 - Close-up view of a small part of the outcrop, showing numerous shells and shell fragments. The whole area shows a similar distribution of fossils. |

|

| Fig. 3 - One of the small echinoids this site is famous for having. The echinoids are called Boletechinus mcglamerii, and are named for one of Alabama’s state paleontologists, Winnie McGlamery, according to Dave Kopaska-Merkel. |

| One of the highlights of the visit was the apparent fossil "claw" held by Alan Collins in Figure 4. The interpretation as a "claw" is not clearcut , however. Dave Kopaska-Merkel (Geological Survey of Alabama) suspects the piece could also be the hinge of a large oyster. |  |

| Fig. 4 - Possible claw (or, alternatively, the hinge of a large oyster), held by Alan Collins. |

| Figure 5 shows a general mix of the types of fossils found at this site in abundance, including internal molds of bivalved mollusks, steinkerns, small scallops, and oyster shells. Larger oyster shells of the genus Exogyra are also found. I originally thought the internal molds were of brachiopods, but Dave Kopaska-Merkel notes that brachiopods have calcite shells while many mollusks have aragonite shells. We mostly see internal molds of these bivalve mollusks because aragonite is much more susceptible to dissolution. |  |

| Fig. 5 - A sampling of the fossils from the site, including oyster valves, internal molds of bivalve mollusks, steinkerns, and a small scallop shell. |

After spending more than an hour at this site in the intense heat, the BPS went to a site on the Tombigbee River where fossils around the K-T boundary are exposed (see Figures 6 and 7). The K-T boundary is the boundary between the end of the Cretaceous period and the beginning of the Tertiary period of Earth history. The site is well-studied and the personal favorite I have heard of Dr. Charles C. Smith of the Geological Survey of Alabama. Dr. Smith has written articles about the site and has published a stratigraphic profile showing the connection between the Late Cretaceous Prairie Bluff Chalk and the overlying Tertiary Clayton Formation. Once we arrived at the site, Dr. Andy Rindsberg (also of the GSA) gave the BPS a brief discussion of the significance of the site and what we could expect to find there. After spending a month in South Africa where fossil collecting is highly regulated, I am, in retrospect, surprised that we are allowed to collect at this site. Still, it was a great pleasure to do this and extremely educational.

|

||

|

| Fig. 7 - View of river facing in opposite direction from Figure 6. |

On looking at the boundary, one readily notices that the fossils below are different from the ones above. Figures 8 and 9 show some of the lower fossils while Figure 10 shows the upper fossils. Oysters from below include Exogyra costata, while those from above include Ostrea pulaskensis ("pulies" for short according to Andy Rindsberg). I think the pulies are the small gray oysters in Figure 10. Figure 9 shows some gastropods, internal molds, and a fragment of a cephalopod shell that I at first thought was a crinoid stem. Also, Figures 8 and 9 show strange fossils, probably connected with large bivalve mollusks, that have a "brain matter" look. According to Dave Kopaska-Merkel, sponges bored into the aragonitic shells of the bivalves, and their borings become filled with calcitic mud. Later, the aragonite dissolved, but the filled borings remained and these preserved the general form of the shells. |

||

|

| Fig. 9 - Cretaceous fossils from closer to the river, including gastropods, internal molds of bivalve mollusks with holes due to boring sponges, and a fragment of a cephalopod shell. |

|

| Fig. 10 - Tertiary fossils from the light gray area, just above the K-T boundary in Figure 6. The small gray shells are Ostrea pulaskensis. |

| The third site the BPS had planned to visit was the oyster fields in the Belmont area. I did not attend this part of today’s trip, but I have been there before, and show in Figures 11 and 12 photographs I took two years ago. The site is absolutely remarkable in the large numbers of giant Exogyra and Pycnodonte oyster shells. A variety of shells are found at this site and are summarized in a pamphlet provided by the GSA. |  |

| Fig. 11 - A field of Late Cretaceous oyster shells, near Belmont, Alabama. |

|

| Fig. 12 - A close-up of a typical area in one of the above fields, showing shells mainly of the genera Exogyra and Pycnodonte. |

In summary, this was a very pleasant and interesting field trip for the BPS. Given how much time many of us have spent at the Union Chapel Mine collecting tracks and plant fossils recently, today’s trip was a nice break from the strip mine rock piles. Thanks to Dave Kopaska-Merkel for comments and revisions to this belated report!