Spring, 2001 - Walker Co, AL

BPS took several trips to an abandoned strip mine, where numerous nodules containing fern spore pods were found. This was on a trip with a visiting paleontologist.

- ‹ previous

- 22 of 22

BPS took several trips to an abandoned strip mine, where numerous nodules containing fern spore pods were found. This was on a trip with a visiting paleontologist.

ANCIENT ALABAMA ANIMAL TRACKS INSPIRE AMATEUR FOSSIL COLLECTORS

TO DOCUMENT FINDS

"The handprints, which include long, curving toes with easily-distinguished pads on the tips, are nearly as big as my own," exclaimed Dr. Jim Lacefield of Tuscumbia. "This was a huge beast. Although I had read that some amphibians reached rather large size in the Pennsylvanian, in all my collecting in Coal Age rocks in Alabama I have never seen any that were anywhere nearly this large," he said.

Lacefield, a part-time biology and Earth science instructor at the University of North Alabama, and author of a recently published book on Alabama fossils, was describing remarkable fossil footprints of an ancient alligator-sized animal that he had collected at a surface coal mine in Walker County owned by the New Acton Coal Mining Company of Warrior, Alabama. Lacefield was visiting the mine on an outing early last year with members of the Birmingham Paleontological Society (BPS), an active group of local amateur fossil hunters who had received permission from the company to salvage fossils from the area.

The mine had been discovered only a few months earlier to be an unusually good source of fossil vertebrate trackways by Ashley Allen, an Oneonta High School science teacher who is also a member of the BPS. A student in Allen's class had alerted him to the site owned by his grandmother, Mrs. Dolores Reid. Fossils connected with vertebrate animal life (that is, animals with a backbone) are of great paleontological significance since they represent some of the most advanced forms of life that developed on Earth at the time and are usually very rare.

Since Allen's discovery, the Walker County mine has been the focus of an extraordinary salvaging effort by BPS members that has led to a remarkable cooperation with professional paleontologists. The trackways collected from the mine are of vertebrate as well as invertebrate animals that lived during the Late Carboniferous Period of Earth history, known to North American geologists as the Pennsylvanian Period. This Period dates back 310 million years to a time when much of the Earth (particularly North America and Europe) was covered with great tropical swamps that eventually laid down many of the vast coal reserves we use today. (In fact, the Pennsylvanian Period is also often referred to as the "Coal Age.") During the past 15 months, mainly through the efforts of the BPS, more than 800 track specimens have been salvaged from the residual rock piles left after the coal mining was discontinued.

According to Dr. Anthony J. Martin of the Department of Environmental Sciences, Emory University, the Walker County mine is "one of the best vertebrate track sites for the time period in question in the world." Martin is an ichnologist, a paleontologist who studies "trace" fossils, or traces of ancient activity. Tracks are trace fossils since they show what an animal was doing but not specifically what it looked like. Martin became involved in the study of the Walker County mine tracks through the insight of Steve Minkin, an Anniston geologist and BPS member who was very active in collecting trackways from the site. Recognizing the scientific importance of the tracks, Minkin proposed a series of meetings at which amateur collectors would bring all of their track finds from the mine to one place for photographic documentation and detailed inspection by professional paleontologists. The first of these events, jokingly dubbed a "Track Meet", was held on August 19, 2000 at the Alabama Museum of Natural History on the campus of the University of Alabama. Dr. Ed Hooks, Museum curator, fully supported the event and was instrumental to its success. The event was also sponsored by the Geological Survey of Alabama. A second meeting, called "Track Meet 2", was held at Oneonta High School on October 14, 2000 to document all finds since the first track meet. The third and final track meet, called "Track Meet 3", will be held on May 12, 2001 at the Anniston Museum of Natural History and will photographically document all tracks found since Track Meet 2 and since the final reclamation of the mine in December, 2000.

Although no fossils of the ancient animals that made the tracks have been found, the trackways record the dynamics of life on land nearly 90 million years before the first dinosaurs walked the Earth. According to Dr. Jack Pashin of the Geological Survey of Alabama, the tracks occur at the head of an area that was once a tidal mud flat much like the one seen today in Mobile Bay. The environment would have been far enough inland to be fresh water rather than salt water, but it would have been an area still dominated by one or more daily tides. At ebb tide, animals would walk or creep across the still wet mud and impress the tracks of their activities. The mud was soft and fine enough that even small creatures could leave well-defined tracks. The best-preserved tracks were probably impressed so deeply that they were buried before they had a chance to be altered in any significant way. Once buried, they were effectively removed from further disturbance for the next 310 million years.

The tidal flat was evidently near a rich forest of tall tree-like lycopods (primitive spore-bearing plants whose foliage resembled that of modern clubmosses), giant horsetails (plants roughly like reeds or bamboo), and tree-sized seed ferns, because among the tracks BPS members also found bark impressions, pith casts, fern impressions, and reproductive organs of a wide variety of ancient plants that are now extinct. It is known that these types of plants could only thrive in fresh-water swamps. Insect life was probably abundant in the forest, and it is significant that one insect fossil was found at the Walker County mine. Dr. Prescott Atkinson, a Birmingham pediatrician and BPS member, found a pair of 4-inch long wing impressions of an extinct relative of modern dragonflies. This is the only fossil found at the site that gives direct information on the actual appearance of a creature that lived in the area. Because of the high quality of many of the plant fossils found at the same site, Track Meet 3 will include a "Plant Fest", where the best plant specimens from the mine will be photographically documented and examined by professional paleobotanists (scientists who study fossil plant life).

Many of the tracks found by BPS members are of amphibians, animals whose modern relatives include frogs and salamanders. These tracks include striking five-toed patterns over a wide range of sizes from less than a centimeter to the size of an adult human hand. Other tracks are those of animals that may be transitional between amphibians and reptiles. Although we do not know precisely what these creatures looked like, they would have been some of the earliest vertebrates to be fully adapted to dwelling on dry land.

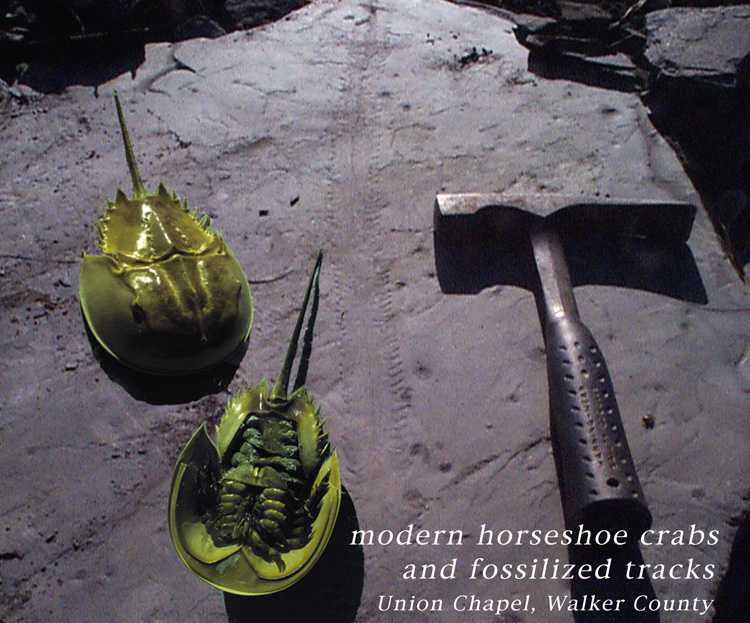

Tracks of other animals, mostly invertebrates, have also been found at the Walker County mine. Apparently, the area was very popular with horseshoe crabs, animals that are related more to scorpions and spiders than to conventional crabs. Today's horseshoe crabs are "living fossils", and the ancient ones that left the tracks probably looked very similar to modern ones. The complex pattern of legs on horseshoe crabs, and the way they walk in water, can explain a wide variety of tracks found at the Walker County mine. Horseshoe crabs in large numbers also left "resting traces", simple impressions of their leg patterns. Evidence also for early fish swimming in shallow areas has been found in the form of wavy tracks where it is thought that fins lightly touched the bottom. Numerous worm burrows have also been found.

All of the trace fossils found at the mine record valuable information on life in the Paleozoic ("ancient life") Era of Earth history. This Era runs from 570 to 245 million years ago, and it was during this time that life on Earth gained a foothold on land. From studies of the tracks brought to the various track meets, ichnologists have deduced that the Walker County mine area was a nursery for many of the animals living there. According to Dr. Andy Rindsberg, an ichnologist working for the Geological Survey of Alabama, the fact that the various tracks occur in a broad range of sizes whose shapes changed slightly as they grew larger points to this interpretation, which is similar to the way modern animals use tidal mud flats today. Rindsberg, along with Martin and his undergraduate student Nick Pyenson, is actively researching the tracks and the team presented talks about them in March to the Southeastern Section of the Geological Society of America.

For the BPS, the discovery of the beautiful trackways has made for a very exciting year. The amateur group, headed by Kathy Twieg of Vestavia Hills (near Birmingham), put a lot of time into salvaging as many tracks as possible before the mine was reclaimed in December. The generosity of the New Acton Coal Mining Company, in particular the enthusiasm of owner Mrs. Reid, was instrumental to the success of the venture. For many of the collectors, the great appeal of the tracks was not only because of their possible scientific value and great beauty, but also because they are more about life than about death. Unlike a pile of bones, tracks record what animals were doing when they were alive. They bring to life an era far removed in time from our own.

For Allen, the Walker County mine experience is part of what being a teacher is all about. "I try to convey to my science students the importance of communication in the scientific community," he says. "I want to be accurate in representing the principles that the scientific enterprise is based upon. Work done without proper communication is called a secret, not a discovery. I feel that any opportunity that I get to show them how to use problem solving skills, scientific reasoning, communication skills, and the ability to put things into a proper social and historical perspective is worth the effort."

The Track Meets themselves represent a rare collaboration between amateurs and professionals that could become a model for other similar finds. "Amateurs are often the source of new discoveries in paleontology," says Rindsberg, who notes that if the BPS had not learned about the site so soon after mining operations ended, any tracks exposed would either have weathered away or been re-buried when the site was reclaimed. He also notes that "if the BPS had not spent so much time looking and splitting open boulders, then the fossils would not have yielded up as much information as they have. Even with the nearly one thousand tracks and trackways that have been labeled so far, Tony Martin and Nick Pyenson have identified some specimens with unique features. If those single specimens had been missed, we would know less about the creatures that made them. At every step of the way, persistence and open-mindedness paid off in this case. I am certain that Alabama has many other surprises for us to find."

To see what some of the tracks look like, click on the following links:

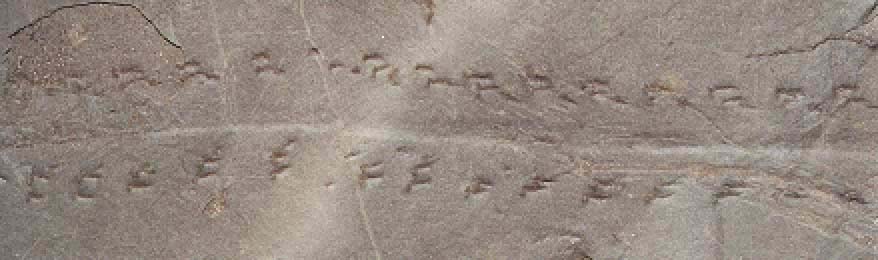

Image 1: Tracks of an amphibian known as Cincosaurus cobbi, a common five-toed animal on the mud flat.

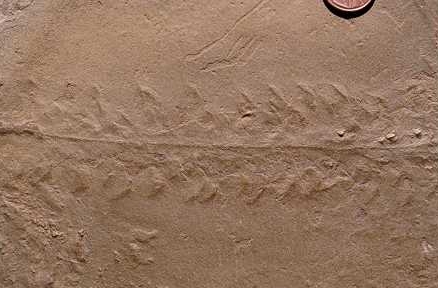

Image 2: Tracks of a larger amphibian, possibly a more grown C. cobbi.

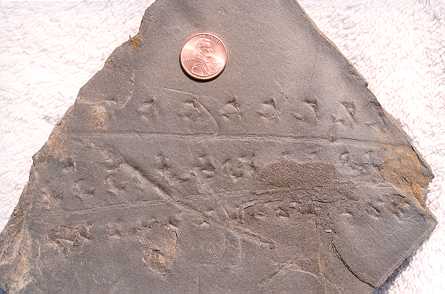

Image 3: Tracks of one of the largest amphibians that walked on the mud flat, known as Attenosaurus subulensis.

Image 4: Tracks of a likely horseshoe crab.

This press release was prepared by BPS member Dr. Ron Buta, a professional astronomer at the University of Alabama. He can be contacted at 205-348-3792 or buta@sarah.astr.ua.edu.

Interested persons may contact Drs. Martin and Rindsberg at the following e-mail addresses:

Dr. Anthony J. Martin - geoam@learnlink.emory.uab

Dr. Andy Rindsberg - ARindsbert@uwa.edu

The following people are either quoted or mentioned above, and may also be contacted for information:

Dr. Jim Lacefield

Dr. Ed Hooks - hooksge@longwood.edu

Dr. Prescott Atkinson - patkinso@uab.edu

by Ron Buta, Department of Physics and Astronomy

University of Alabama

Tuscaloosa, Alabama

The Union Chapel Mine is now known to be one of the best Lower Pennsylvanian track sites in North America. During December, the mine was in the process of reclamation, and the BPS returned one more time as a group to search for trackways among turned-over spoil piles in one of the most productive areas of the site. About 15 BPS members and several newcomers attended the field trip on a pleasant mid-December day.

When we arrived at the site, only one small area was not reclaimed. This particular area was one which had yielded many good tracks in the past and so we were all delighted to see that the mine workers had moved some of the old rock piles around, allowing us to see if any new material had been exposed. In spite of this, we all had difficulty finding any new high quality tracks. Nevertheless, there were still tracks to be found. I found the interesting specimen shown in Figure 1. It appears to be the trackway of an arthropod, where each track is a small roundish spot. In the significant collection of track photos which the BPS "track meets" have provided, I had not seen another set like this one. I also found the tracks shown in Figures 2 and 3. |

|||

|

|||

|

|||

| On the reclaimed areas and in the overturned area, one can still find nice plant fossils at this site. Figure 4 shows an especially nice set of ferns from a split rock. Most interesting is how strong the stem of these ferns is.

|

|||

Figure 5 shows brown ferns of the genus Neuropteris, which was common at this mine.

|

|||

Figure 6 shows a single large seed impression of a seed fern. This is how such seeds are often found.

|

|||

However, I found another rock in the overturned area having more than a dozen seed impressions. Several of these are shown in Figure 7.

|

|||

The ferns they are associated with are shown in Figure 8. Jim Lacefield discusses the seeds of seed ferns on page 66 of his new book, "Lost Worlds in Alabama Rocks", and gives a wonderful general discussion of the Coal Age in Alabama and what happened to the seed ferns.

|

|||

The reclamation of the Union Chapel Mine caps off a spectacular year of discovery for the BPS, and the Union Chapel experience marks the beginning of a remarkable cooperation between BPS amateur rock collectors and two professional organizations, the Geological Survey of Alabama and the Alabama Museum of Natural History on this new project. The more than 500 track specimens salvaged by BPS members and guests since January 23, 2000 are currently being researched by professional paleontologists. Hundreds of high quality plant fossils were also salvaged and will eventually be studied. We will no doubt be talking about the experience for years to come.

General

On August 19, the Birmingham Paleontological Society (BPS), the Alabama Museum of Natural History, and the Geological Survey of Alabama will hold an all day session in Smith Hall at the University of Alabama to photograph and label Pennsylvanian age trackways collected from the Union Chapel Mine in Walker County, Alabama. The Alabama Museum of Natural History will host the event and provide refreshments and lunch to everyone involved. Persons with tracks/trackways are asked to arrive at Smith Hall around 9:00 am to begin set up for photographing and labeling. The photography, specimen labeling, and data recording will last until around 5 pm Saturday afternoon. From 11:00 to 12 noon, there will be a break for a series of short talks that will address the group on the geology of the Union Chapel Mine and the significance of collecting these Paleozoic trackways.

This "Track Meet" is a unique opportunity to document most of the trackways that have been taken from the Union Chapel Mine, collected mainly during the year 2000. The purpose of this session is:

- To compile a photographic record of the Union Chapel Mine trackways,

- To document the owners of tracks/trackways in the event a researcher needs to study these specimens in the future. A photographic catalogue is planned for the publication of this data and will be titled BPS Monograph # 1.

- To permanently label all specimens collected at the Union Chapel Mine. These labels will be affixed to the back side of the specimen, not interfering with the track/trackway.

It is requested that people bring only tracks/trackways from the Union Chapel Mine for the August 19 Track Meet. Also, plant fossils from the Union Chapel Mine should not be brought to be photographed at this session. There will a separate photo session for plant fossils collected at the Union Chapel Mine. Likewise, trackways from other Alabama locations collected by the BPS would also be the subject of a future photo session.

It is also requested that each specimen brought to the Track Meet for photography be thoroughly cleaned before unloading the specimen at the registration table. This cleaning should be done by the specimen(s) owner before arriving at Smith Hall. If calcite scale is present, a bit of vinegar poured onto the shale for 10-15 seconds may remove some of it, if the vinegar is gently worked over the surface with a soft toothbrush. Be extremely gentle with the specimen because vigorous scrubbing the specimen with water/vinegar will destroy the track/trackway.

Agenda

9 am to 11:00 am: Registration, triage, preparation of permanent labels, photography

11:00 am to 12:00 noon: Speakers

- Ed Hooks, Alabama Museum of Natural History:

- Welcome

- The Importance of the Amateur Paleontologist

- BPS Display Case

- Kathy Twieg:

- Address from the President to the Birmingham Paleontological Society

- BPS Monograph Series

- Andrew K. Rindsberg, Geological Survey of Alabama:

- Donation of Pennsylvanian Trackways to Geological Survey of Alabama for their Educational Outreach Program and Permanent Collection; Ethics in Collecting, Trading, and Selling Fossils

- Jack Pashin, Geological Survey of Alabama:

- Geology of the Pottsville Formation and its relation the Union Chapel Mine

12:00 noon to 1:00 p.m.: Lunch (provided by BPS)

1:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m.: Photography and preparation of permanent labels

Registration, Triage, and BPS Data Base

Upon arriving at Smith Hall at the beginning of the Track Meet Saturday morning, each person will be greeted at the registration desk set up outside the front of Smith Hall. Labeling and filling out data base forms will also be done outside the front of Smith Hall. In the event of inclement weather, registration, triage, data base work, and labeling will all take place inside Smith Hall, on the 1st floor. Volunteers will be available to help specimen owners unload and carry specimens to Smith Hall from the parking area. If a person has specimens for the photo shoot, the person should be registered by a BPS host at the front table. Upon signing in, the person will present his/her specimens to be photographed. Andy Rindsberg, Geological Survey of Alabama, will evaluate each sample for photography priority. Those track/trackway specimens of the highest quality will be given a red dot and receive first priority for the photo shoot. The second quality tracks/trackways will be given a blue dot and will be photographed later if time allows in the afternoon. Specimens of minor value to this effort will be given a green dot, and if the owner prefers, may be donated to the Geological Survey of Alabama for their educational outreach program. A depot for such specimens will be marked. Conversely, there will be trackways that the Alabama Museum of Natural History or Geological Survey of Alabama consider of high value to scientific research. If this is the case, Andy will place a yellow dot on the specimen and request donation of the specimen to the Museum or Survey for their permanent collections, again, at the discretion of the owner. In addition, Ed Hooks (Alabama Museum of Natural History) will request that several of the most important trackways be displayed in the BPS display case in Smith Hall for a 4-6 month duration, after which time the specimens will be returned to their owners. These specimens will also receive a yellow dot.

Once Andy Rindsberg has graded track/trackway specimens with red, blue, or green dots, a Track Meet volunteer will give the owner of the specimen(s) to be photographed a series of unique numbers, one number for each rock specimen. Next, the volunteer will give the owner a data sheet on which the owner shall list the necessary data for each track/trackway. The information on this data sheet will be:

- Collector’s name

- Taxon (ichnogenus and ichnospecies, if known)

- Date collected (month/year)

- Location collected (Union Chapel Mine)

- County location (Walker County, Alabama)

- Geologic formation (Pottsville Formation)

- Geologic Age(Pennsylvanian)

- Unique sample number (e.g. UCM –1)

All that the specimen owner needs to write on the data sheet(s) are: his/her name, specimen name, and date collected. These data sheets will be pre-printed with the standard site information (categories d-h).

Labeling

After the data sheet has been filled out, the owner with the assistance of a Track Meet volunter, will move the track/trackway specimens to a table where permanent labels are being attached to the rock. The rock will be turned over and a permanent label will be affixed to the back side of the rock by a Track Meet volunteer. This label will be a postage stamp-sized white label, and another volunteer will take the data sheet and print the necessary information on the permanent label on the rock with a black indelible pen. The permanent label on the rock should read:

- Unique sample number

- Taxon (ichnogenus and ichnospecies, if known)

- Date collected

- Location collected

- County location

Finally, the volunteer will give the owner a temporary label to be attached to the specimen with two way cellophane tape. All that is written on the temporary label is the specimen’s unique sample number within the range of UNC-001 to UNC-500. This temporary label will be attached to the specimen for the photograph; after which it may be discarded. However, it is critical that this paper label stay attached to the rock specimen until after the track/trackway is photographed.

Transport of Specimens to the 2nd Floor for Photography and Data Input

Another Track Meet volunteer will assist the owner in transporting the specimens to the 2nd floor of Smith Hall for photographing. There are two large classrooms on the 2nd floor of Smith Hall where the specimens, in their boxes, must be staged prior to the photo shoot. In one classroom, a camera table and artificial lighting have been arranged for the photo session. Once the specimens have been photographed, the owner will place the specimens back in the staging area and attach a "post-it" to the specimen box indicating that photographs have been taken.

In another classroom where the specimens will also be also staged, Prescott Atkinson will be using a computer to input information about the samples into the BPS database.

The owner will take the data sheet to Prescott to enter specimen data in the database. Track Meet volunteers will assist in transporting the rock specimens downstairs and back to the owner’s vehicles, after the photo session and data input are finished.

There will probably be many tracks that will not brought to the August 19 "track meet". The labeling session at the "track meet" should demonstrate to everyone the importance of labeling the Union Chapel Mine specimens and how everyone should label their additional specimens not brought to the August 19 Track Meet.

Photo Session

Ricky Yanaura, Staff Photographer for the University of Alabama, has provided technical assistance to the Alabama Museum of Natural History and the BPS on how to best photograph the track/trackway specimens. He recommends using 35 mm print film, in a camera mounted on a tripod in a large classroom on the second floor of Smith Hall. A camera table will be positioned in one corner of the classroom and serve as a stationary base to place the rock specimens for photography. The camera can be raised or lowered depending on the size of the specimen. Ricky will supply all artificial lighting and a series of lighting reflectors to capture the best possible lighting contrast for the rock specimen. The Alabama Museum of Natural History will furnish all the film and pay for the film developing. Ron Buta will be the photographer for the track meet and will use a Nikon 35 mm camera with a macro lens. Ron will have a volunteer to assist him throughout the entire photo session. Ron and Ricky will get together a few days in advance to practice a dry run for the lighting and camera table set up on the second floor of Smith Hall.

Each specimen may be lightly sprayed with water before the photo shoot to enhance rock contrast in order to see the track/trackway more clearly. A metric bar scale will be placed next to each specimen for each photograph. The temporary label shall be arranged properly on the rock specimen for the photo shoot.

Others are welcome to also photograph track/trackway specimens with their own cameras/digital cameras while the specimens are being photographed for the BPS Monograph by Ron Buta.

Security

Security will be provided by volunteers to ensure that the general public does not enter the museum while the museum is closed. In addition, the BPS will provide volunteers to ensure the security of all track/trackway specimens during the August 19 Track Meet.

Media

The Alabama Museum of Natural History has invited the local media to cover the August 19 Track Meet.

Volunteers

Currently, 13 persons have volunteered to work all day at the Track Meet. Twelve volunteers are needed at a very minimum to operate this event. Anyone who would like to help with the Track Meet is strongly encouraged to volunteer. The BPS and the museum would really appreciate it.

Housekeeping

Two Track Meet volunteers will assist to ensure that the building and grounds of Smith Hall are properly policed for debris, trash, and disposable lunch and refreshment materials. This will be most important if it rains and registration, triage, and labeling have be done inside Smith Hall. These volunteers will also assist with serving lunch.

Lunch, Refreshments

Coffee, drinks, and pastries will be served during the day. Lunch will consist of chicken/sausage gumbo, rice, French bread, and a touch of filé. There will be no charge for lunch or refreshments.

Department of Physics and Astronomy

University of Alabama

Tuscaloosa, Alabama

The New River Mine is a surface mine which was spotted by Jim Lacefield in early February this year, and shortly thereafter Jim and I scouted the site out. As expected, the site included plant fossils, but one difference compared to other sites that Jim noticed was an abundance of fossils of Artisia, the pith of the gymnospermous tree known as Cordaites. The only other sites where I have seen Artisia fossils are the Kimberly surface mine (see BPS report for May 29, 1999), and another mine near Eldridge that the BPS visited with Wayne Canis's class in March 1998.

|

| Figure 2 View of a rock wall roughly on the east side of the site. |

| Bruce Relihan was the first to find an interesting specimen of Artisia, shown in the picture here. Artisia is characterized by horizontal ridges along the pith, which can be found in cast form as well as impressions, much like a Calamites pith. The specimen Bruce found appears to be either an impression or a highly flattened cast. The ridged area is framed by a larger area obviously affected by the plant. This frame must indicate the true extent of the trunk. |  |

| Figure 3 Artisia specimen found by Bruce Relihan. |

| Other types of fossils found were bark impressions of arborescent lycopods. I show pictures of two different types here. One appears to be of the type Lepidodendron obovatum, with very large leaf scars. I am not certain about the type of the other piece shown, other than it is also likely to be a Lepidodendron. |  |

| Figure 4 Bark impression of Lepidodendron obovatum, with large, distinct leaf scars. |

|

| Figure 5 Bark impression of another likely type of Lepidodendron. |

| The last pieces I illustrate are ones I found in February during my scouting visit with Jim Lacefield. One appears to be a mostly unflattened cast of a branch of Calamites. The piece shows 15 strong, indented nodes, and I must say it resembles a petrified tootsie roll! I am not sure of the species of this Calamites, but I did find a type of Calamites at this site that I was able to identify. I found highly compressed cast pieces of what I think is Calamites suckowi, one of the more common species of this genus. |  |

| Figure 6 Cast fossil of a branch of Calamites, with 15 clear nodes. |

After a couple of hours of searching with limited results, trip attendees decided to return to Union Chapel Mine, about 30 miles east of the New River site. Union Chapel Mine is so rich that it continues to yield good specimens even though many people have visited the site the past 4 months. It is a good site to fall back on when other sites do not live up to expectations. See the reports for January 23, March 19, and May 28, 2000 for information on this mine.

Department of Physics and Astronomy

University of Alabama

Tuscaloosa, Alabama

| It was decided at the March meeting that the BPS should return to this mine once again as an organized field trip. As I have noted in previous reports, this is a site the BPS visited with great success just two months earlier. The site is rich in footprint fossils of Pennsylvanian amphibians and other creatures. Although the previous organized visit, on January 23, occurred on a rather bleak day, it was nothing like the one today. Rain fell hard all day across most of Alabama and never let up even for a few minutes. Because of the weather, only six people turned up for this outing. |  |

| Figure 1 Unusual tracks of one or two large creatures that must have been moving in very wet mud. |

| In spite of the weather, several of us still found nice tracks and other fossils. I show a few that I picked up here. One large set of tracks I found was lying at the bottom of a rock pile that had been thoroughly searched. After the tracks were cleaned of mud, it looks to me like they are amphibian tracks that were laid down in rather wet mud. The impressions are wide as the creatures' whole body probably sloshed in the mud. There are two sets of tracks on the main piece, and details of one are shown in the close-up. |  |

| Figure 2 Close-up of part of the previous specimen, showing likely toe prints flanking the broad body scrape. |

A much smaller set of tracks I found in a different area has small y-shaped prints in a bit of a random pattern. In Museum Paper No. 9 of the Alabama Museum of Natural History (authors Aldrich and Jones), a creature that produced similar tracks is known as Bipedes aspodon. At least two sets of tracks are also present on this piece. Bipedes aspodon is described by Aldrich and Jones as an animal with only two toes. Although Aldrich and Jones clearly considered the creature to be an amphibian, BPS members who found similar tracks felt they are more likely to be tracks of an arthropod. |

I found some other interesting and larger tracks on a large rock on the well-searched rock piles. I suspected tracks might be inside at a deeper level in this rock. The rock had interesting deposits or formations that covered different layers, but it was not clear what these features might be. After removing many layers of the rock, I did indeed find four footprints of a modest-sized creature which, according to Museum Paper No. 9, is an amphibian known as Quadropedia prima. Aldrich and Jones state that the creature is higher in the scale than most of the species they illustrated in their article, because it walked more like later reptiles. They point out the presence of a distinct pad, which we can see in the pictures I show here. The four prints could be detected at several different layers, and at least one of the prints was well-defined at all of the layers. The appearance of the prints seemed different at different layers, suggesting that some of the variety in the prints we have been finding at the site is due in part to the different layers that were exposed. |

||

|

| Figure 5 Two tracks of the same creature, the one at right being the same foot as in the previous picture, but the print looks different because it is at a different level. At this level, only three toes are seen, with a strong pad. |

Other Notes on the Union Chapel Site January 23-March 19, 2000

The Union Chapel Mine was visited many times by BPS members and guests between January 23 and March 19. Ashley Allen brought to the February BPS meeting a huge rock with a set of excellent large amphibian prints. Bruce Relihan brought to the March BPS meeting a large stump cast of a likely Lepidodendron. The stump is more than a foot in diameter and tapers around the edges, as if it were near the bottom of the original trunk. Bruce related the heroic effort he put into getting the huge fossil by himself, which involved building a rock ramp to allow him to get it into his truck. Steve Minkin also brought to the last BPS meeting an excellent set of modest-sized tracks found by his wife.

All in all, the Union Chapel site elicited such great interest and finds that Steve Minkin asked Ed Hooks if the BPS could have a temporary display case at the Alabama Museum of Natural History in Tuscaloosa. Ed agreed to this and some of the new Union Chapel pieces may soon be on display for the public to see!

On this first field trip of the first year of the new millennium (or the last year of the old millennium), the BPS had the pleasure of visiting a truly interesting surface mine in Walker County. The Union Chapel Mine is smaller than the Cedrum Mine we visited last month, but is located in the same general area. The field trip was attended by 11 "diehards" who were not put off by the weather, which started out rainy and cold. By the time we arrived at the site (about 9am), the rain had completely subsided and we were virtually rain-free the whole time we were there. However, the clouds persisted and the day was a little gloomy.

The trip was arranged by Ashley Allen, who heard about the site through his science class. The site proved particularly rich in tracks of amphibians and probably arthropods from the lower Pennsylvanian subdivsion of the Carboniferous Period. The tracks are trace fossils of the footprints of the creatures, and it is clear from the variety of tracks we all found that many different species of creatures are represented. According to Jim Lacefield, track fossils are found at most of the lower Pennsylvanian sites in Alabama, but often they are not as obvious or as richly abundant and diverse as they are at Union Chapel Mine. Like Cedrum and other Pennsylvanian sites the BPS has visited the past year, Union Chapel Mine is also rich in plant fossils. Jim has told me that the mix of other fossils with the usual plants reflects more the environmental differences between sites, rather than significant age differences. |

|

| Fig. 2 - One of the rock piles at the site that was rich in tracks. |

| The following pictures show a few of the track fossils found. These range from some fairly large tracks (a few centimeters per print) to smaller prints that look like Chinese characters, and finally to really small prints that are at most a couple of millimeters or less in size. Some tracks also included obvious tail dragging marks. These can straight or curved, and I recall that Ashley found a particularly wavy specimen. Virtually everyone who was there found one or more interesting track fossils. |  |

| Fig. 3 - Excellent amphibian tracks held by Matthew Valente. |

|

| Fig. 4 - Tracks resembling Chinese characters. |

|

| Fig. 5 - Two sets of small tracks, with likely tail dragging marks. |

|

| Fig. 6 - Inverse tracks of unknown creature. |

| Probably the most spectacular prints from the site were a huge set found by Jim Lacefield, the "likes of which I had never seen", according to Jim. Jim relates the following:

"The handprints, which include long, curving toes with easily-distinguished pads on the tips, are nearly as big as my own. This was a huge beast. Although I had read that some amphibians reached rather large size in the Pennsylvanian, in all my collecting in Coal Age rocks I have never seen any that were anywhere nearly this large." A digital photo of Jim's specimen is shown here. |

|

| Fig. 7 - Monster tracks found by Jim Lacefield, in an image prepared for inclusion in his book. |

Although the track fossils were superb, and were the principal things we all searched for, the plant fossils were also quite impressive and ranked as my favorites. Bark impressions of Lepidophloios, a subgenus of the Lepidodendrales, were especially abundant at this site. Jim Lacefield was seeing so much Lepidophloios that he was wondering if there was any Lepidodendron. However, both Sigillaria and Lepidodendron were well represented at the site. I show specimens of Sigillaria and a genus related to Lepidodendron here. By far the most beautiful of any specimens I have seen, at Union Chapel or any other site, were the compressed cast fossils of two branches of a Sigillaria species. The leaf scars are small hexagons with a central spot, and are so well-preserved that even fine ridge-like details are seen. I spent 45 minutes hammering on a large rock to get pieces of these branches out. On the same rock was an especially beautiful species that looks at first like a Lepidodendron, with pieces of highly compressed cast fossils lying about. According to Jim Lacefield, this might be a representative of a related genus called Diaphorodendron. |

|

| Fig. 9 - Close-up of Sigillaria specimen |

|

| Fig. 10 - Bark impression of a likely Diaphorodendron, a genus related to Lepidodendron. |

| Other items of interest were a snail fossil found by Kathy Twieg, a large Lepidophloios cast found by Ashley Allen, a rhizome of Calamites by Jim Lacefield, myself, and others, a small medullary cast of Calamites found by Bruce Relihan, and a gigantic lycopod stump (probably weighing more than 800 pounds) noticed by Jim Lacefield Jim also showed me a likely trace fossil of a hermit crab and also tiny insect prints. Concerning the rhizome of Calamites, Jim gave me the following comments: "Calamites, like all horsetails, propogates vegetatively through spreading by underground stems called rhizomes. New Calamites stems sprout upward from these horizontal, underground stems. It's a type of asexual reproduction that allows them to spread quickly into new territory and also anchors them firmly in the unstable ground along rivers and out onto newly deposited delta sediments. Those round structures were clusters of cells that, under the right conditions, could develop into new Calamites shoots. The rhizomes of Calamites look quite similar to the stems in most cases, but have nodes that get progressively closer together as they get out approach the apical area (the growth tip that spreads outward through the soil. | |

|

|

| Fig. 11 - Part of a rhizome of Calamites , showing characteristic round features that are not normally seen on calamites branch casts. |

|

| Fig. 12 - Huge stump cast fossil, probably 800 pounds in weight, probably of a lycopod. |

There is no question that Union Chapel Mine has been one of the most interesting fossil sites that the BPS has had the privilege of visiting. According to Ashley, the Union Chapel Site will be reclaimed very soon. Since our original visit, various subgroups of BPS members have been back to the site, trying to salvage as many tracks and other items as possible before the site is gone.

Additional Pictures from Union Chapel Mine

The following pictures provide more examples of the types of fossils found at the Union Chapel Mine. In the two weeks after the January 23 field trip, several of us returned to the site. These are some of the items found on these return trips.

|

| Fig. 1 - Stump cast of a Lepidophloios arborescent lycopod. Jim Lacefield and I were exploring one of the popular track rock piles at the site, and he pointed out this excellent stump cast to me. The piece weighs close to 300 lbs, but fortunately it lay on a slope that was accessible by my truck. All one could do is move the thing downhill. I rolled it down about 25 feet of slope onto a dirt embankment, and then with help moved it into my truck. It is pictured in my backyard garden area. |

|

| Fig. 2 - this is a different view of the same stump cast, showing the large indentation that seems to characterize the shape of the trunks of these trees. In the January 23 report, I show a picture of an 800 lb stump with a similar indentation. |

|

| Fig. 3 - this piece shows two criss-crossing tracks from small creatures with no tail-dragging marks. |

|

| Fig. 4 - two sets of small tracks with distinct tail-dragging marks. |

|

| Fig. 5 - complex inverse tracks of a still different creature, with only a weak tail dragging mark. |

|

| Fig. 6 - a single large inverse print of what must have been a massive creature. This could have been a type of Attenosaurus, although the print is really different from those shown in Museum paper No. 9 of the Alabama Museum of Natural History, by Aldrich and Jones, published in 1930. |

|

| Fig. 7 - excellent set of small inverse prints with a weak tail-dragging mark. |

|

| Fig. 8 - another lycopod stump, this time covered with excellent leaf scars on side facing camera. Weighs about 200 lbs |

|

| Fig. 9 - three sets of small prints, found on a "page" of a vertically standing rock that opened into many layers. |

|

| Fig. 10 - a set of tracks, nearly 2 feet long, found by Jim Lacefield. Jim believes these are fossil tracks of a horseshoe crab. The actual crabs were not in the original photo! |

|

| Fig. 11 - Jim also found this rock with excellent fossils of lycopod branches. Details are present at various levels and the branching is complex. |

|

During this field trip, the BPS had the pleasure of returning to the Cedrum Surface Coal Mine near Jasper in Walker County, Alabama. Although we had visited this mine only a few months ago (see BPS field trip report for July 24, 1999), there was a sense of urgency connected with our latest visit. The Drummond Company, which operates the mine, was going to shut down operations on December 30, which would then be followed by the normal reclamation effort to restore the area. This meant that the large "spoil piles" we explored in July would soon be gone. Thus, it was decided that we should go back one more time before the reclamation effort to look for plant fossils.

As in July, this visit was hosted by a mine engineerwho instructed us in issues of safety in the mine area. We were delighted to have his wife join us this time and bring several parents and students of various ages who are involved in home schooling. They all seemed to enjoy learning about fossils and to be excited about finding and collecting them. During this visit we had about 30 BPS members and guests in attendance, a larger than average group. There were so many cars that we were asked to carpool a little to miminize the number of cars in the pit. |

|||

|

I must say that I enjoyed this visit much more than the visit in July. The highlight of the visit in July was our tour of the mining operation and our visit to the "dragline." However, it was so hot that day that fossil collecting was difficult and a little unpleasant. Our focus this time was only on fossil collecting, and the day was cool, calm, a little cloudy, and very pleasant for climbing and searching the rock piles. We also collected in a different area from our July visit. One problem we encountered was that it was rather dry, and the movement of trucks combined with dryness caused the rocks to be very dusty, making it a little difficult to notice the fossils. Thus, it was not especially easy to find good fossils.

Many of the fossils that attendees did find were very good. I can describe a few that I brought home. Being a little slow in heading towards the main rock piles, I stopped at a rock that others had seen but had passed up because of its size. The rock included a foot-long Calamites pith impression that I thought was interesting because it includes about 20 nodes. There is more than just the pith, however. The pith is surrounded by a wider pattern that may give the true dimension of the trunk, since the sediment was obviously impacted by the plant over this wider area. The specimen looked much better after it was cleaned, and I show a picture of it here. |

Bruce Relihan found a large rock on a pile that turned out to have a variety of fossils in it, which he generously shared with me. The main fossils in the rock were Sphenopteris ferns of high quality, but also I was impressed to see excellent specimens of Spenophyllum, a genus of small land plants with wedge-shaped leaves. The shape of Sphenophyllum is a circular pattern with radial pinnules. I show two types of likely Sphenopteris ferns here. The first has very thin pinnules and reminds me of Sphenopteris elegans, shown in a book: "Plant Fossils of West Virgina" by Gillespie et al. (1978). The second is a beautiful, larger fern that looks different but I think is still the same genus. |

|

|

Don McDonald found a rock with what looked like nice specimens of Asterophyllites, one of the forms of the foliage connected with Calamites. The rock was very large and it was difficult to extract intact pieces.

This was a common problem because much of the rock at this site is shale, and splitting rocks means some fossils may break or even disintegrate. This nearly happened to me on the next fossil I found. Near where Don was working, I found the interesting fossil shown here. It broke up when I started to try and extract it, but the pieces could be put together like a puzzle as in the photograph. At first, I thought this was a Calamites impression, but the long striations and the narrowing of the fossil towards its end reveals this to be a giant strap-shaped leaf of Cordaites. Note the lack of any nodes, which rules out the Calamites interpretation completely. Matthew Valente, who came as a guest with Jim and Faye Lacefield, found a round-leafed fossil fern that I had not seen before. Matthew tentatively identified it as Mariopteris robusta. According to Jim, this is a common species near the south part of the well-known Warrior Basin, but it is not common in Walker County where Cedrum is located. This field trip was combined with our traditional "Christmas season gathering" and several members brought the fixings for our lunch that were shared by everyone. Thanks to Jim Lacefield and James Lowery for comments and additions to this report, and especially to Steve Minkin and his son for making and bringing the delicious gumbo as our main course! --Edited by Vicki Lais |

Photos by Larry Hensley

|

| Cedrum Surface Mine in Walker Co., Alabama, Dec. 18, 1999 -- BPS Members in the Huge Dragline Bucket |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Department of Physics and Astronomy

University of Alabama

Tuscaloosa, Alabama

This field trip was a very special one for the BPS. We visited a surface coal mine in Walker County. About 20 BPS members and guests attended the trip, which occurred on one of the hottest and most humid days of the year thus far.

This is one of the largest surface coal mining operations in the state. The area is part of the major Pottsville Formation, and is also known as the Warrior Basin. The BPS was hosted by Mr. Hendon, a mine engineer, who also brought his son along. Mr. Hendon first gave us a basic description of the mine, its history, its extent, and the geology of the area. He then took us on a tour of the mine, allowing us to park near a monster machine known as a "dragline". To access the coal seams, overlying soil and hard rock has to be removed, which is the principal task of the dragline. Usually there are 100-200 feet of solid rock to be removed, but on Saturday the dragline was mostly removing topsoil.

|

--Edited by Vicki Lais

In summary, this was a really great field

|