Visitor

trackways

July 31, 2005 - Pennsylvanian Fossils, Walker Co, AL

One of the more interesting finds of the day was a young kitten, living in a cave in the wall. It had apparently not eaten in quite a while, as it was nothing but a pile of bones. Several members fed her, and this friendly, loving little kitten now has a good home with Jan and Greg.

(Pictures courtesy Steve Corvin and Vicki Lais.)

Looking over the site, trying to decide where to start.

Lea digging through the rubble.

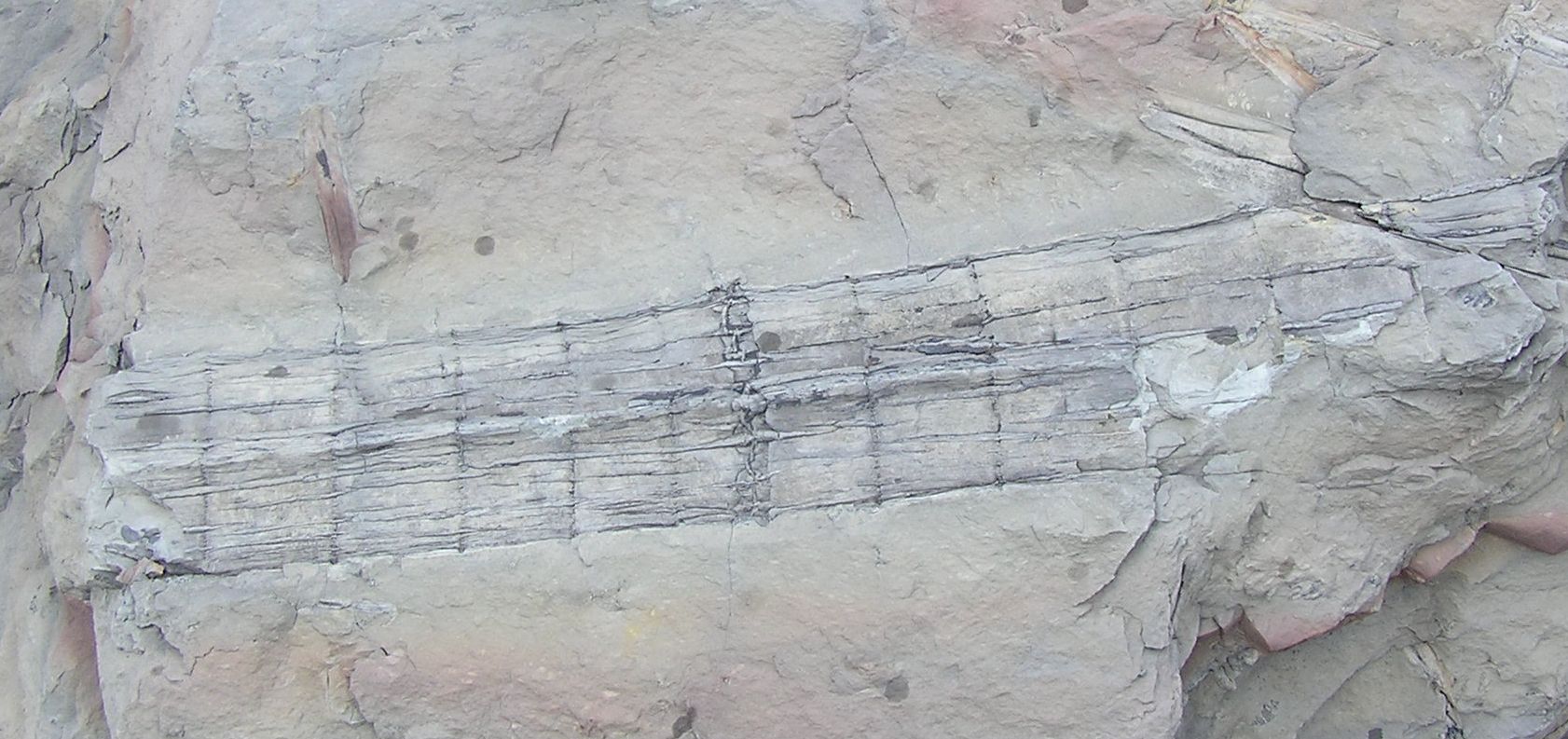

Calamites - an impression and an inside mold.

Lea found a slab with a nice starfish cast.

A closer look at Lea's starfish.

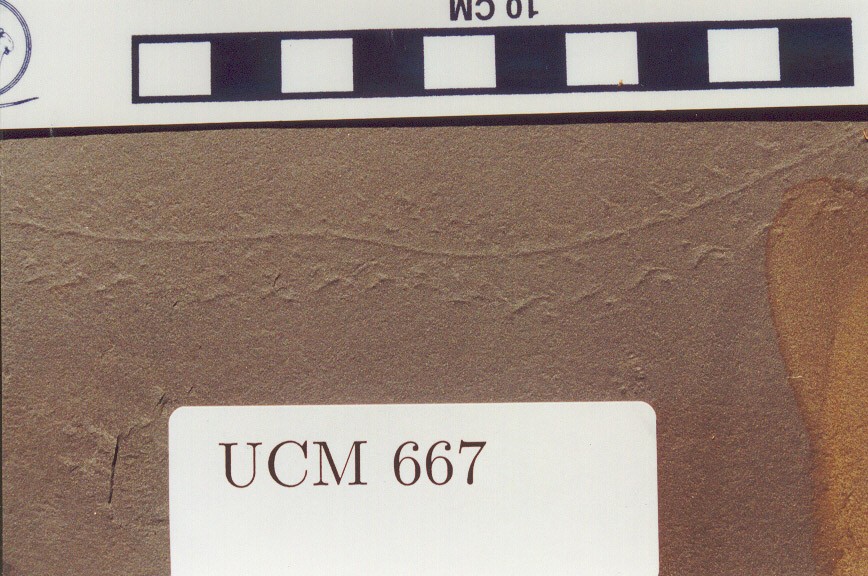

Possible raindrops and other trace fossils. Many of the fossil finds at this site were impressions on boulders too large to carry home.

These are impressions of lepidodendrum and calamites.

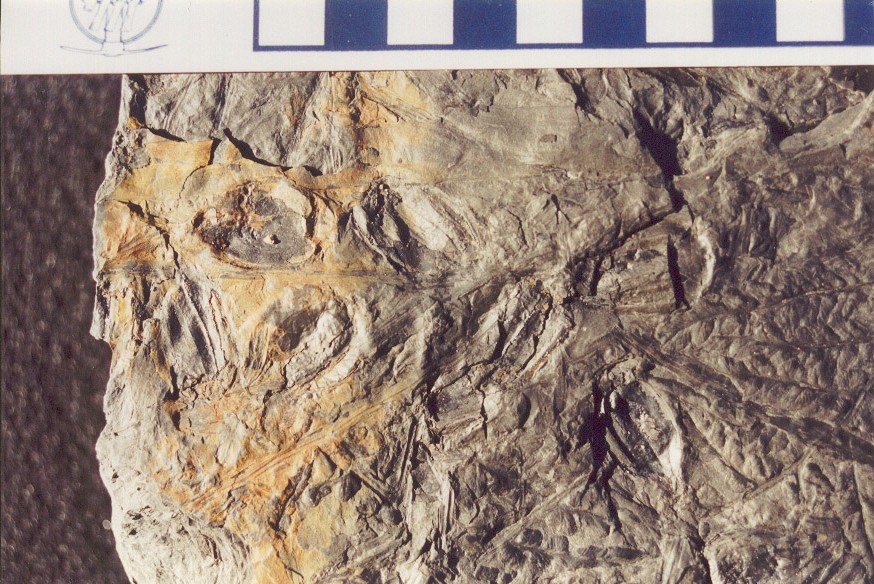

Bill found this slab of shale with several starfish impressions. He graciously allowed Greg to break it apart and shared it with other members.

A closer view of the slab. There are at least 6 starfish on this slab.

Bill found the large slab containing several starfish. This is the piece he kept. Thanks for sharing such a wonderful find, Bill!

More plant impression fragments.

We found this newest member living in a cave in the rocks (the kitten, if you had to ask!), and nothing but skin and bones. We fed her and made a friend for life - Jan and Greg took her home to live with them.

June 21, 2003 - Carboniferous Fossils, Jefferson Co, AL

BPS members visited 2 areas of new road development and a small quarry in Jefferson County this month, making 3 stops total. We had not visited these locations before, so were not sure how prolific the sites would be.

(Photos courtesy Greg Mestler, Ron Beerman, and Vicki Lais.)

At stop #1, several brachiopods and a couple of slabs with small amphibian track prints were found.

Jan found a number of brachiopods at this spot.

At stop #2, a number of nice limpets (gastropods) were found.

How's this for service? First time we ever had roadside delivery!

At stop #3, a number of plant fossils were found at a local quarry.

|

Picture of Calamites found just above a coal seam at one of the sites visited. It measures 101mm in diameter (approx 4 inches) and 304 mm (12”) in length. This cast of the central pith-cavity of the trunk is a very common fossil of Calamites. It is characterized by the articulation and the vertical ribbing between the nodes. The ribs are the imprints of the vascular strands. It measures 101mm in diameter (approx 4 inches) and 304 mm (12”) in length. This tree, in size up to 20 meters, grew during the Carboniferous period, about 320-350 million years ago. (This specimen found by Ron, Claire got the other half, which is about the same size.) |

|

Stigmaria Ficoides. This is a fossilized root of the Sigillaria tree. This piece measures 102 mm by 114 mm. It was found near a coal seam. This plant lived during the Pennsylvanian Period of the Paleozoic Era 320-350 mya around swamps or lakes grew to several meters in height. Its modern day relatives are the small club mosses and lycopods. The round nodes on the surface of stigmaria are scars where rootlets were once attached and arranged in a radial fashion about stigmaria like the bristles of a bottle brush. During their life these trees shed parts of their outer bark.

Possibilities - a spore case, or Neuropteris leaf.

Leisa & Winnie discussing the current find.

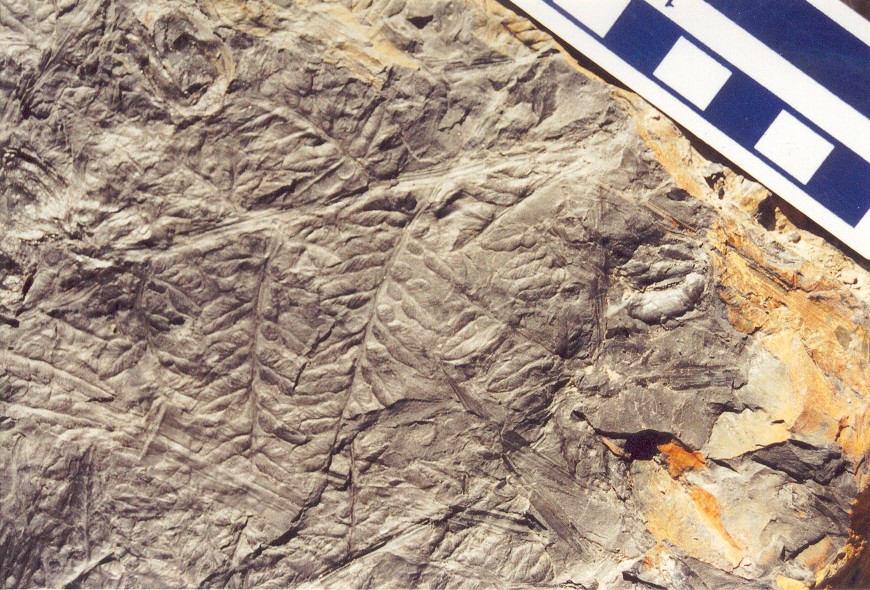

Some fern material found at the site is shown below.

July 3, 2002 - UCM Press Release

Press Release

WORLD-CLASS FOSSIL DISCOVERY IN NORTHWEST ALABAMA

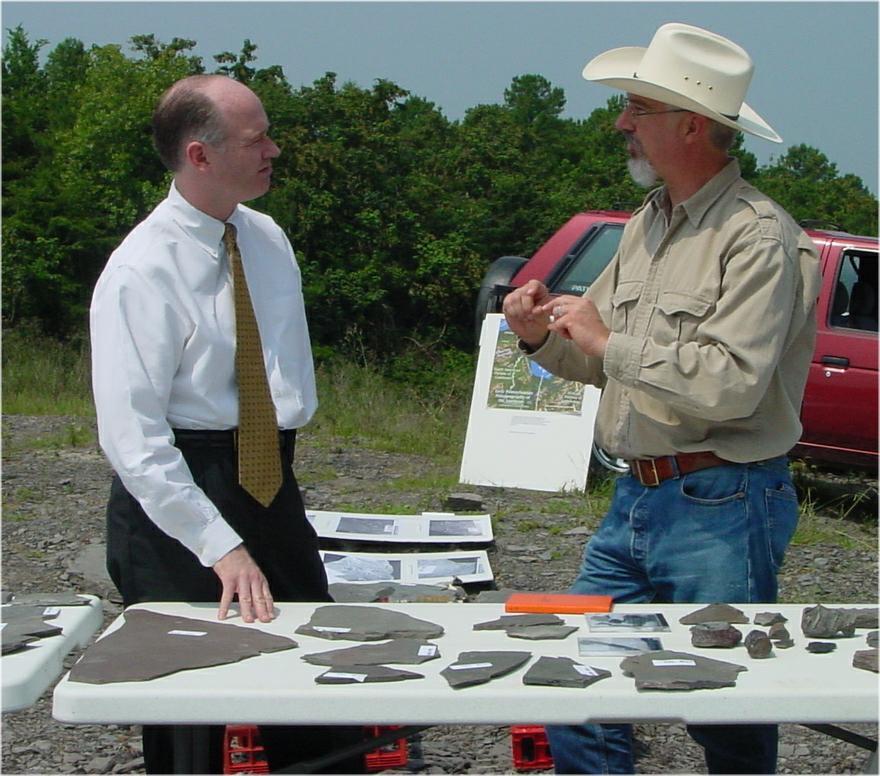

Just prior to the July 4th holiday last week, U.S. Representative Robert Aderholt (District 4) visited an extraordinary fossil discovery just northwest of Birmingham in Walker County. Hosting Rep. Aderholt and his aide Bill Harris in a tour of the site were members of the Birmingham Paleontological Society (BPS), a local amateur fossil group, and a number of professional geologists and paleontologists who have participated in studying the fossils that have been recovered so far from the site.

“This is the most important discovery of Carboniferous Period tracks known; there is no comparable site in the world,” stated Prescott Atkinson, a physician at Children’s Hospital and a member of the BPS. He was quoting from a letter sent to Rep. Aderholt from Professor Hartmut Haubold, a German paleontologist who is widely considered one of the world’s leading experts on fossil animal tracks. Professor Haubold had written to Representative Aderholt in support of protecting the fossil site for scientific research after seeing the photographic database of more than 1300 track specimens compiled by Dr. Ron Buta, a University of Alabama astronomy professor and BPS member. Prof. Haubold’s assessment of the site: “by quantity, by quality, and by geological age, it is the most important discovery of Carboniferous tracks hitherto known.” This assessment was further strengthened in another letter sent to Representative Aderholt by renowned fossil track specialist Jerry MacDonald (author of Earth’s First Steps: Tracking Life Before the Dinosaurs), who visited the Walker County site in April 2002. In the late 1980’s Mr. MacDonald found an extensive pre-dinosaur tracksite in New Mexico that dates from the Permian Period, some 30 million years “younger” than the Walker County site.

Picture 1: Paleontologist Dr. Andy Rindsberg explains fossil tracks to Representative Aderholt

Picture 2: Rep. Aderholt and his aide Bill Harris (center) examine fossil tracks with Drs. Atkinson (L) and Rindsberg (R)

During the tour of the area, Dr. Jack Pashin, a coal geologist with the Geological Survey of Alabama, discussed the ancient history of the rocks at the site. The sediment (mud, dirt, and sand) that became shale rock and the plant material that became coal were laid down there about 310 million years ago in a swampy river delta during the Carboniferous Period (“Coal Age”), many millions of years before the dinosaurs. Dr. Jim Lacefield, adjunct professor at the University of North Alabama and author of Lost Worlds in Alabama Rocks, continued with the ancient history of the area, explaining that this part of Alabama was near the equator when these sediments were deposited. He explained that an ocean covered much of North America to the west and south of the present day location of Walker County. Dr. Andy Rindsberg, a paleontologist with the Geological Survey of Alabama, took Aderholt and Harris around several tables to examine specimens of vertebrate and invertebrate tracks that have been recovered from the site, some that very morning. Vertebrate tracks ranged from smaller than a fingernail to larger than a hand. Bruce Relihan, Curator of Horticulture with the Birmingham Zoo and a member of BPS, showed the Congressman some examples of the many plant fossils that the site has yielded and presented him with a small amphibian trackway, found that morning at the site. Steve Minkin, a geologist with Westinghouse in Anniston, finished the tour by explaining that there are several acres of undisturbed strata at the site, and that preservation of the site could be accomplished by including an engineered design to leave the undisturbed track-bearing rock prepared for a proper paleontological excavation.

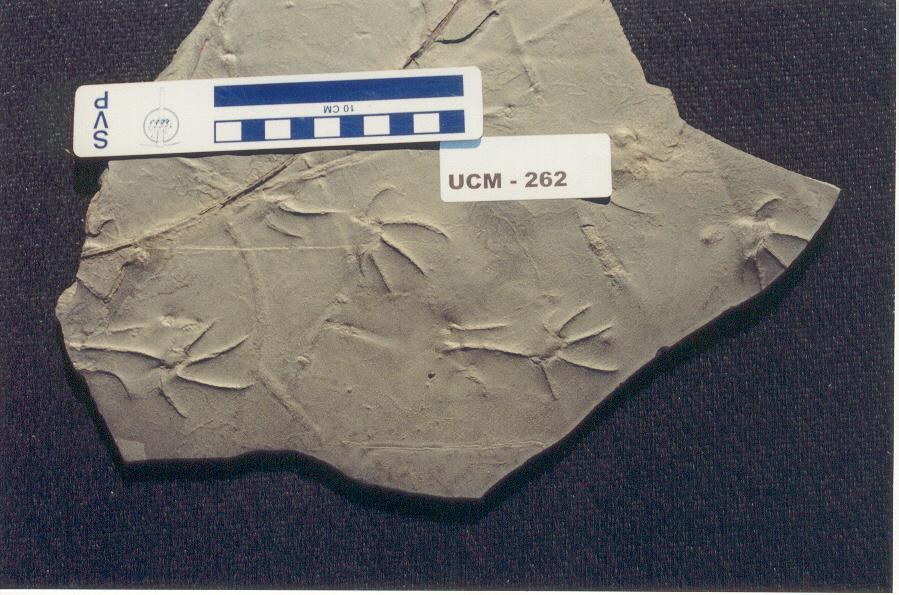

Picture 3: Large fossil amphibian trackway

Picture 4: Fossil amphibian trackway

Picture 5: Fossil fish scale

The site is located at a small surface coal mine owned by the New Acton Coal Company, and the group expressed their appreciation for the generosity of the company in allowing this world-class collection of fossil tracks to be assembled from broken rock in the spoil areas. If the undisturbed rock beds still remaining in the site are properly excavated in the future, the testimony of the experts indicates that the scientific and educational value of the site will be of truly international significance. In fact, several school field trips have already taken place at the site under the supervision of Ashley Allen, an Oneonta High School science teacher. Mr. Allen, also a BPS member, originally discovered the tracks after being led to the site by one of his students, the grandson of Mrs. Delores Reid, owner of New Acton Coal Company. Together the BPS fossil enthusiasts and their professional collaborators are proposing that the site could be developed as an important regional attraction for Alabama, with easy access from U.S. Highway 78 and, soon, Corridor X. A small building onsite could serve as a museum and visitor’s center that would house many of the tracks already collected, plus tracks excavated during a future paleontological dig. Similar to other sites out West, a pre-fabricated, portable building could be placed over an ongoing excavation and serve to protect the research and allow school classes and the public to observe paleontologists at work.

Much work remains before the vision of saving the site can be realized. Representative Aderholt is considering introducing legislation that would preserve the site for future scientific development. Alabama has already entered scientific history as home to a world-class Coal Age track site, and even more discoveries may lie ahead.

For further information, please contact

Dr. Andy Rindsberg (205-349-2852, e-mail: arindsberg@gsa.state.al.us)

Dr. Prescott Atkinson (205-934-7054, e-mail: patkinso@uab.edu)

Dr. Ron Buta (205-348-3792, e-mail: rbuta@bama.ua.edu)

March 5, 2001 - Press Release - Ancient Alabama Animal Tracks

ANCIENT ALABAMA ANIMAL TRACKS INSPIRE AMATEUR FOSSIL COLLECTORS

TO DOCUMENT FINDS

"The handprints, which include long, curving toes with easily-distinguished pads on the tips, are nearly as big as my own," exclaimed Dr. Jim Lacefield of Tuscumbia. "This was a huge beast. Although I had read that some amphibians reached rather large size in the Pennsylvanian, in all my collecting in Coal Age rocks in Alabama I have never seen any that were anywhere nearly this large," he said.

Lacefield, a part-time biology and Earth science instructor at the University of North Alabama, and author of a recently published book on Alabama fossils, was describing remarkable fossil footprints of an ancient alligator-sized animal that he had collected at a surface coal mine in Walker County owned by the New Acton Coal Mining Company of Warrior, Alabama. Lacefield was visiting the mine on an outing early last year with members of the Birmingham Paleontological Society (BPS), an active group of local amateur fossil hunters who had received permission from the company to salvage fossils from the area.

The mine had been discovered only a few months earlier to be an unusually good source of fossil vertebrate trackways by Ashley Allen, an Oneonta High School science teacher who is also a member of the BPS. A student in Allen's class had alerted him to the site owned by his grandmother, Mrs. Dolores Reid. Fossils connected with vertebrate animal life (that is, animals with a backbone) are of great paleontological significance since they represent some of the most advanced forms of life that developed on Earth at the time and are usually very rare.

Since Allen's discovery, the Walker County mine has been the focus of an extraordinary salvaging effort by BPS members that has led to a remarkable cooperation with professional paleontologists. The trackways collected from the mine are of vertebrate as well as invertebrate animals that lived during the Late Carboniferous Period of Earth history, known to North American geologists as the Pennsylvanian Period. This Period dates back 310 million years to a time when much of the Earth (particularly North America and Europe) was covered with great tropical swamps that eventually laid down many of the vast coal reserves we use today. (In fact, the Pennsylvanian Period is also often referred to as the "Coal Age.") During the past 15 months, mainly through the efforts of the BPS, more than 800 track specimens have been salvaged from the residual rock piles left after the coal mining was discontinued.

According to Dr. Anthony J. Martin of the Department of Environmental Sciences, Emory University, the Walker County mine is "one of the best vertebrate track sites for the time period in question in the world." Martin is an ichnologist, a paleontologist who studies "trace" fossils, or traces of ancient activity. Tracks are trace fossils since they show what an animal was doing but not specifically what it looked like. Martin became involved in the study of the Walker County mine tracks through the insight of Steve Minkin, an Anniston geologist and BPS member who was very active in collecting trackways from the site. Recognizing the scientific importance of the tracks, Minkin proposed a series of meetings at which amateur collectors would bring all of their track finds from the mine to one place for photographic documentation and detailed inspection by professional paleontologists. The first of these events, jokingly dubbed a "Track Meet", was held on August 19, 2000 at the Alabama Museum of Natural History on the campus of the University of Alabama. Dr. Ed Hooks, Museum curator, fully supported the event and was instrumental to its success. The event was also sponsored by the Geological Survey of Alabama. A second meeting, called "Track Meet 2", was held at Oneonta High School on October 14, 2000 to document all finds since the first track meet. The third and final track meet, called "Track Meet 3", will be held on May 12, 2001 at the Anniston Museum of Natural History and will photographically document all tracks found since Track Meet 2 and since the final reclamation of the mine in December, 2000.

Although no fossils of the ancient animals that made the tracks have been found, the trackways record the dynamics of life on land nearly 90 million years before the first dinosaurs walked the Earth. According to Dr. Jack Pashin of the Geological Survey of Alabama, the tracks occur at the head of an area that was once a tidal mud flat much like the one seen today in Mobile Bay. The environment would have been far enough inland to be fresh water rather than salt water, but it would have been an area still dominated by one or more daily tides. At ebb tide, animals would walk or creep across the still wet mud and impress the tracks of their activities. The mud was soft and fine enough that even small creatures could leave well-defined tracks. The best-preserved tracks were probably impressed so deeply that they were buried before they had a chance to be altered in any significant way. Once buried, they were effectively removed from further disturbance for the next 310 million years.

The tidal flat was evidently near a rich forest of tall tree-like lycopods (primitive spore-bearing plants whose foliage resembled that of modern clubmosses), giant horsetails (plants roughly like reeds or bamboo), and tree-sized seed ferns, because among the tracks BPS members also found bark impressions, pith casts, fern impressions, and reproductive organs of a wide variety of ancient plants that are now extinct. It is known that these types of plants could only thrive in fresh-water swamps. Insect life was probably abundant in the forest, and it is significant that one insect fossil was found at the Walker County mine. Dr. Prescott Atkinson, a Birmingham pediatrician and BPS member, found a pair of 4-inch long wing impressions of an extinct relative of modern dragonflies. This is the only fossil found at the site that gives direct information on the actual appearance of a creature that lived in the area. Because of the high quality of many of the plant fossils found at the same site, Track Meet 3 will include a "Plant Fest", where the best plant specimens from the mine will be photographically documented and examined by professional paleobotanists (scientists who study fossil plant life).

Many of the tracks found by BPS members are of amphibians, animals whose modern relatives include frogs and salamanders. These tracks include striking five-toed patterns over a wide range of sizes from less than a centimeter to the size of an adult human hand. Other tracks are those of animals that may be transitional between amphibians and reptiles. Although we do not know precisely what these creatures looked like, they would have been some of the earliest vertebrates to be fully adapted to dwelling on dry land.

Tracks of other animals, mostly invertebrates, have also been found at the Walker County mine. Apparently, the area was very popular with horseshoe crabs, animals that are related more to scorpions and spiders than to conventional crabs. Today's horseshoe crabs are "living fossils", and the ancient ones that left the tracks probably looked very similar to modern ones. The complex pattern of legs on horseshoe crabs, and the way they walk in water, can explain a wide variety of tracks found at the Walker County mine. Horseshoe crabs in large numbers also left "resting traces", simple impressions of their leg patterns. Evidence also for early fish swimming in shallow areas has been found in the form of wavy tracks where it is thought that fins lightly touched the bottom. Numerous worm burrows have also been found.

All of the trace fossils found at the mine record valuable information on life in the Paleozoic ("ancient life") Era of Earth history. This Era runs from 570 to 245 million years ago, and it was during this time that life on Earth gained a foothold on land. From studies of the tracks brought to the various track meets, ichnologists have deduced that the Walker County mine area was a nursery for many of the animals living there. According to Dr. Andy Rindsberg, an ichnologist working for the Geological Survey of Alabama, the fact that the various tracks occur in a broad range of sizes whose shapes changed slightly as they grew larger points to this interpretation, which is similar to the way modern animals use tidal mud flats today. Rindsberg, along with Martin and his undergraduate student Nick Pyenson, is actively researching the tracks and the team presented talks about them in March to the Southeastern Section of the Geological Society of America.

For the BPS, the discovery of the beautiful trackways has made for a very exciting year. The amateur group, headed by Kathy Twieg of Vestavia Hills (near Birmingham), put a lot of time into salvaging as many tracks as possible before the mine was reclaimed in December. The generosity of the New Acton Coal Mining Company, in particular the enthusiasm of owner Mrs. Reid, was instrumental to the success of the venture. For many of the collectors, the great appeal of the tracks was not only because of their possible scientific value and great beauty, but also because they are more about life than about death. Unlike a pile of bones, tracks record what animals were doing when they were alive. They bring to life an era far removed in time from our own.

For Allen, the Walker County mine experience is part of what being a teacher is all about. "I try to convey to my science students the importance of communication in the scientific community," he says. "I want to be accurate in representing the principles that the scientific enterprise is based upon. Work done without proper communication is called a secret, not a discovery. I feel that any opportunity that I get to show them how to use problem solving skills, scientific reasoning, communication skills, and the ability to put things into a proper social and historical perspective is worth the effort."

The Track Meets themselves represent a rare collaboration between amateurs and professionals that could become a model for other similar finds. "Amateurs are often the source of new discoveries in paleontology," says Rindsberg, who notes that if the BPS had not learned about the site so soon after mining operations ended, any tracks exposed would either have weathered away or been re-buried when the site was reclaimed. He also notes that "if the BPS had not spent so much time looking and splitting open boulders, then the fossils would not have yielded up as much information as they have. Even with the nearly one thousand tracks and trackways that have been labeled so far, Tony Martin and Nick Pyenson have identified some specimens with unique features. If those single specimens had been missed, we would know less about the creatures that made them. At every step of the way, persistence and open-mindedness paid off in this case. I am certain that Alabama has many other surprises for us to find."

To see what some of the tracks look like, click on the following links:

Image 1: Tracks of an amphibian known as Cincosaurus cobbi, a common five-toed animal on the mud flat.

Image 2: Tracks of a larger amphibian, possibly a more grown C. cobbi.

Image 3: Tracks of one of the largest amphibians that walked on the mud flat, known as Attenosaurus subulensis.

Image 4: Tracks of a likely horseshoe crab.

This press release was prepared by BPS member Dr. Ron Buta, a professional astronomer at the University of Alabama. He can be contacted at 205-348-3792 or buta@sarah.astr.ua.edu.

Interested persons may contact Drs. Martin and Rindsberg at the following e-mail addresses:

Dr. Anthony J. Martin - geoam@learnlink.emory.uab

Dr. Andy Rindsberg - ARindsbert@uwa.edu

The following people are either quoted or mentioned above, and may also be contacted for information:

Dr. Jim Lacefield

Dr. Ed Hooks - hooksge@longwood.edu

Dr. Prescott Atkinson - patkinso@uab.edu

December 16, 2000 - Pennsylvanian Fossils, Walker Co, AL

by Ron Buta, Department of Physics and Astronomy

University of Alabama

Tuscaloosa, Alabama

The Union Chapel Mine is now known to be one of the best Lower Pennsylvanian track sites in North America. During December, the mine was in the process of reclamation, and the BPS returned one more time as a group to search for trackways among turned-over spoil piles in one of the most productive areas of the site. About 15 BPS members and several newcomers attended the field trip on a pleasant mid-December day.

When we arrived at the site, only one small area was not reclaimed. This particular area was one which had yielded many good tracks in the past and so we were all delighted to see that the mine workers had moved some of the old rock piles around, allowing us to see if any new material had been exposed. In spite of this, we all had difficulty finding any new high quality tracks. Nevertheless, there were still tracks to be found. I found the interesting specimen shown in Figure 1. It appears to be the trackway of an arthropod, where each track is a small roundish spot. In the significant collection of track photos which the BPS "track meets" have provided, I had not seen another set like this one. I also found the tracks shown in Figures 2 and 3. |

|||

|

|||

|

|||

| On the reclaimed areas and in the overturned area, one can still find nice plant fossils at this site. Figure 4 shows an especially nice set of ferns from a split rock. Most interesting is how strong the stem of these ferns is.

|

|||

Figure 5 shows brown ferns of the genus Neuropteris, which was common at this mine.

|

|||

Figure 6 shows a single large seed impression of a seed fern. This is how such seeds are often found.

|

|||

However, I found another rock in the overturned area having more than a dozen seed impressions. Several of these are shown in Figure 7.

|

|||

The ferns they are associated with are shown in Figure 8. Jim Lacefield discusses the seeds of seed ferns on page 66 of his new book, "Lost Worlds in Alabama Rocks", and gives a wonderful general discussion of the Coal Age in Alabama and what happened to the seed ferns.

|

|||

The reclamation of the Union Chapel Mine caps off a spectacular year of discovery for the BPS, and the Union Chapel experience marks the beginning of a remarkable cooperation between BPS amateur rock collectors and two professional organizations, the Geological Survey of Alabama and the Alabama Museum of Natural History on this new project. The more than 500 track specimens salvaged by BPS members and guests since January 23, 2000 are currently being researched by professional paleontologists. Hundreds of high quality plant fossils were also salvaged and will eventually be studied. We will no doubt be talking about the experience for years to come.